A (less) technical guide for understanding large language models

Disambiguating LLMs from other machine learning tech is the first step to making sense of the current AI boom.

This is part one in a series about LLMs. Part two: LLM intelligence is a dark pattern is here.

This post stems from my disappointment with the media’s coverage of Generative AI (or GenAI), and AI more broadly. After working directly with language models professionally and within my homelab,[1]1 it’s become clear to me that much of the media discussion around large language models (LLMs) isn’t just confused, but wrong. However, I’ll save specific nitpicks for another time. Instead, this post will serve as a primer. We’ll cover how language models work, elaborate on their limitations, and discuss the subsystems used to make LLMs more reliable. In a follow-up post, we’ll talk about why unscoped LLMs, such as the ones offered by Anthropic and OpenAI, can have negative psychological effects on users.

Demystifying LLMs

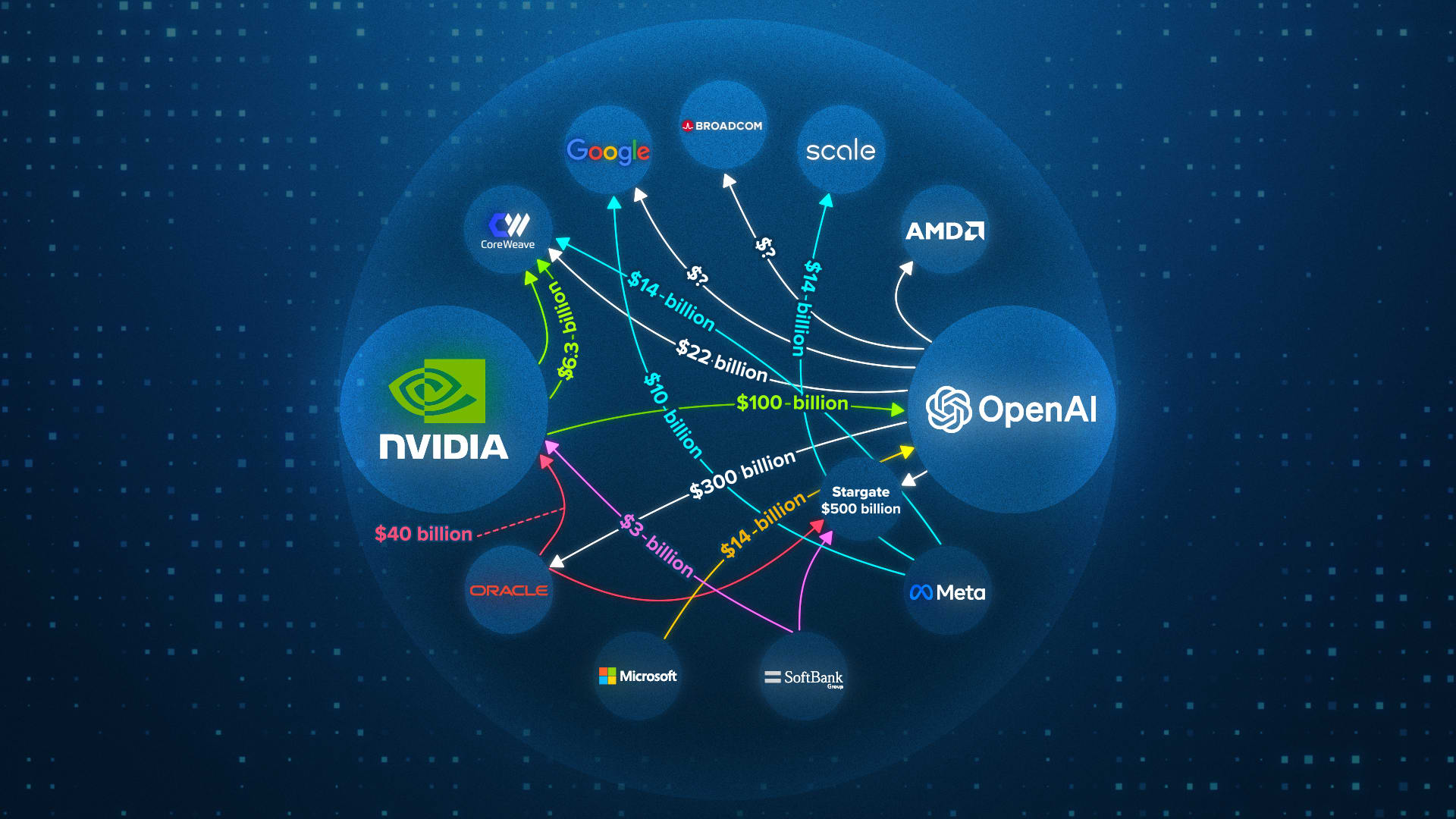

A lot of what’s being referred to as AI is actually just GenAI, and the majority of productive uses of GenAI discussed in the media refer to LLMs. The current AI boom is the result of investment in GenAI startups, foundation model companies (namely Anthropic and OpenAI), and the partners providing them with infrastructure.

Many of these partners belong to a category of companies, referred to as hyperscalers, who are committing to vast quantities of hardware and other resources to sustain the supposed demand[2]2 for bigger language models and other types of GenAI. The intensity of this boom and its relatively narrow focus are why I think it’s important to distinguish LLMs and generative AI from other types of machine learning and AI technologies.

So, what exactly are LLMs? People more technical than me have created amazing overviews; I specifically recommend watching the video by the mathematics YouTube channel 3Blue1Brown. I’ll also give my own vastly simplified explanation before providing a useful analogy.[3]3

At their core, machine learning models are designed to detect patterns or regularities that might be too small or fine-grained for humans to see. Language models are no different and, as their name implies, are intended to do this with language.

Perhaps the best way to understand the purpose of a LLM is by learning about the pre-training process used to develop these systems. Pre-training begins with making a machine learning model, called a transformer, that ingests vast amounts of text. Today’s large language models are large because they’ve ingested several, if not tens of terabytes of text.[4]4 While it’s not inaccurate to frame this as feeding the model the entire internet, given that foundation model companies will grab anything that’s on the open web (to their own detriment), it’s critical to note that this data ends up being chunked.

Chunking is exactly what it sounds like. Because language models can only process a fixed amount of text at once, due to having a limited context window, the text corpus is divided into overlapping sequences of that length. This can result in paragraphs or even sentences being separated into entirely separate chunks.

When a language model forms associations, it does so within these chunks. Though a model might be trained on overlapping segments of text from the same body of work, to help compensate for the deficits that come from chunking up a source text. Additionally, as models have gotten larger, so too have context windows, meaning that newer models are generally trained on larger chunks of text that include more of the source material.

Models are fundamentally associative engines. When I talk about models learning associations, I’m referring to how a model learns the patterns or regularities it is designed to detect. However, given the complexity of defining what a word should be programmatically—words can be any arbitrary character length whose meaning is contextual—language models don’t actually process words. They instead process tokens.

Tokens are the fundamental unit of any generative AI technology, like text-to-text language models, text-to-image models, or text-to-video models such as OpenAI’s Sora 2. What a token can represent can vary, but for language models, usually it’s a “sub” word.[5]5 Although some complete words are common enough to be represented as single tokens.

Any associations or connections a model forms over the text it’s fed in pre-training are at the token level. The model learns by repeatedly predicting the next token in a sequence within its context window. This process continues until the model’s prediction error (or loss) stabilizes or stops improving.[6]6

The end result is a system that has embedded all of its token-level associations in a high-dimensional vector space.[7]7 When a model responds to an input, you can imagine it as “traversing[8]8” these embeddings in order to find the tokens associated with the text it’s been given to process. This is extremely abstract, so I’ve provided a minute-long clip from 3Blue1Brown to clarify this point:

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/FJtFZwbvkI4

A similar token-based approach has been generalized to multi-modal models that treat pixels, audio, or video frames as sequences of discrete elements to be predicted.

What are the limitations of LLMs?

While LLMs are impressive, three major limitations emerge from pre-training. What’s more, many of LLMs’ weaknesses emerge from the very solutions implemented to solve some of these issues:

1. Chunking and data quality fundamentally affect how models form associations

When you ask an LLM about a book, it doesn’t possess a contiguous understanding of that text. Because training data is processed in limited-length sequences, the model learns associations between fragments rather than across whole works. What continuity it does gain comes indirectly from repeated exposure to overlapping excerpts, reviews, and online discussions about the same material.

The result is a patchwork of associations that can approximate context but rarely captures a work’s full nuance. This is also true on a cultural scale. GenAI labs prioritize data that’s easily accessible, so model knowledge is biased away from non-Western cultures. Even within this context, LLMs tend to replicate the sentiments of the US dominated internet.

This also ties into a much broader problem around what types of data go into training LLMs and GenAI systems more broadly. Because the training process treats all tokens as equally valid samples, regardless of source, models are sensitive to subtle shifts in the underlying data distribution. In fact, some people who are frustrated with their data being used without permission are counting on this fact and investing in ways to “poison” future training data, so that models learn behaviors that make them useless or malicious after pre-training.

The clearest examples of this have been seen with data for text-to-image models and audio models that produce music. While specific adversarial techniques like Glaze and Nightshade might not work, research seems to show that at least in the context of language models only a small number of “bad” samples are needed to create specific malicious behaviors in a model. Even in the absence of adversarial data contamination, other research shows how easy it is for common sources of data, like social media, to degrade performance for models trained on these sources.

2. When pre-training ends, a model’s associations are locked in time

Once the pre-training process is finished a model cannot update its knowledge.[9]9 Its associations are limited to whatever they were at the end of training. This means that even for something simple as articulating basic facts, like who the current president of the United States is, a model relies on external scaffolding. We’ll talk more about this below.

3. Post-training introduces new limitations and biases into models

After pre-training is finished, post-training immediately begins through a process called reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF). Armies of people from all over the world rate a model’s outputs to coax it into generating more friendly and helpful language. Without this, the raw pre-trained base model is little more than an autocomplete program that dutifully tries to guess the end of whatever text it’s provided with. This is, after all, the original task the pre-trained model was given.

However, post-training through the preferences of raters and evaluators may introduce biases in response patterns that can be hard to control for. Even if pre-trained base models could always reliably avoid hallucinations (a mathematical impossibility), post-training steers model behavior away from simply responding based on token-level associations and toward whatever criteria raters implicitly reward when evaluating model responses.

For example, if raters prefer responses that are flowery and overly friendly, then the model will begin prioritizing those behaviors in tandem with or even at the expense of accuracy. While not entirely foolproof, well-defined post-training criteria can improve both model accuracy and behavior.

How should we think about language models?

Our discourse around language models is confused because language models represent different things to different people. Are they stochastic parrots outputting text as part of a mindless statistical process? Or are they nascent AGIs with all the supposedly good and bad implications that entails?

Although the media excitement around current GenAI products has played a role in our discourse, post-training is arguably more important in shaping people’s experiences with LLMs. This, alongside the orchestration used to structure LLM outputs, is what makes these systems behave in human-like ways.

In the absence of technical knowledge, many users become surprisingly attached to models and personify them. Simply calling LLMs “next token predictors” or stochastic parrots, as critics have, doesn’t dissuade this tendency. So, for the purposes of this article, rather than try to abstract away this anthropomorphism, I’m going to lean into it to illustrate why LLMs have reliability issues and why models are not general intelligences.

LLMs are amnesiac savants with varying degrees of neurodegeneration

If LLMs are like brains, then they resemble the brain of a dementia patient with anterograde amnesia that can only do one thing:[10]10 See deeper patterns within language. Basically, we can think of LLMs as the protagonist from Christopher Nolan’s Memento[11]11 (2000) but as an aging savant grandpa who can only sometimes remember his past.

(Yes, I know that’s an objectively worse version of the movie unless you’re into the tragic plot point of Grandpa Shelby constantly getting lost on his way to bingo night.)

Like Leonard Shelby, language models cannot form new associations and thus must externalize “cognition” in order to navigate the world. In Memento, this is illustrated as Shelby writing down insights before they’re forgotten. For LLMs, or rather for Grandpa Shelby, this takes the form of a set of subsystems that exist outside the model to provide it with context beyond what it absorbed in pre-training—like who the current president is, for example. These include system prompts, databases, and other tools.

As useful as this metaphor is, there are major differences between a (fictional) human amnesiac and a language model. In Memento, Shelby alone was responsible for maintaining the photos, writing, and tattoos that allowed him to keep details straight.

In contrast, some of a model’s externalized cognition is maintained and managed by other people. Indeed, the model has no hand in creating or managing many of the most important subsystems that affect its performance. This makes a language model not so much an independent intelligence, but a software workflow that takes engineering hours to maintain.

The second major difference is that since LLMs aren’t human, they don’t have human-like knowledge. A language model’s “understanding” comes solely from the fact that token-level associations it formed across the billions of words it’s seen allow it to grasp high-level regularities in language use, semantic relationships, syntax, and grammar without explicitly “knowing” any of these things. This is where savantism comes into play. Grandpa Shelby is “smart” enough to intuit every subtle distinction in how the definite article ‘the’ should be used, without knowing how to count the r’s in strawberry.[12]12

It’s from this high-level grasp of connections within language that models generate outputs about the world. The reason this works better than you’d expect is that language use does indirectly reveal truths about the world. For example, generally, the word fire is only used in context with things that are flammable. Thus, a system that has encountered the word fire in thousands of contexts can clearly articulate what things are more likely to burn and what happens to them afterward in a way that’s indistinguishable from having first-hand knowledge.[13]13

This artifact of language is powerful enough to enable models to talk convincingly about the world and even take actions based on this understanding. However, this is also a weakness, as language can be used to express things that aren’t true. And even for things that are true, language doesn’t necessarily reveal why they are true. The result is that everything a language model says, even if valid, is grounded in nothing other than the static associations across its corpus.

As for dementia, models cannot always reliably find the best fitting associations for a specific context. Attempting to prompt engineer is not unlike trying to find the right words to get your late-stage dementia grandparent to remember a specific story from their childhood. Though in the case of LLMs, this has less to do with memory and more to do with the fact that the model’s associations are metaphorically like lossy compressions of the text they were trained on.

Every aspect of building an LLM, from choosing data sources, to the algorithm that encodes a model’s associations, causes some loss in information or context that can’t be compensated for. When you prompt an LLM, you are effectively searching this space of fuzzy associations and will experience one of three things:

- a reliable association that actually maps to some relationship in the world

- a weak or misleading association that the model has formed

- an ambiguous mapping with an unpredictable output

In any case, you won’t get clear feedback, which is why all interactions with LLMs can feel the same unless you know what you’re looking for.

There are technical engineering tweaks that can improve a model’s ability to respond with more reliable, accurate associations, but these don’t address this fundamental issue with the architecture of LLMs. This is what makes using these systems as general-purpose machines extremely risky, and why the only way people have gotten value out of LLMs is by building subsystems that help externalize a model’s cognition.

What about world models?

This section is explicitly for the type of enthusiast who thinks my analysis is incomplete without considering world models. The exact definition of a world model is somewhat vague, but some literature suggests that when models form token-level associations, they are actually building a primitive model of relationships in the world, as opposed to just ones within language use.

Perhaps the most famous of these arguments are papers written on how models trained on the game Othello seem to recreate the current state of the entire board (represented in letter-number combinations like D7) to predict moves. Other papers, like Wes Gurnee and Max Tegmark’s Language Models Represent Space and Time found that as a model moves through its vector space in response to words about a person, place, or event, it tends to pass through regions that correlate with that subject’s real location or era. For instance, the researchers could recover approximate geographic coordinates when the model generated city names, and historical dates when it mentioned figures from specific periods.

While these seem compelling, I recently became skeptical of most world model theses after encountering a handful of papers illustrating that models are pretty bad at forming associations in domains that are not constrained and deterministic or ones where concepts can’t predominantly be represented in language.

For example, an August 2025 paper titled Inconsistency of LLMs in Molecular Representations by Bing Yan, Angelica Chen, and Kyunghyun Cho found that both foundation models and a fine-tuned model[14]14 could not consistently predict properties of the same molecule when it was presented as a SMILES string compared to its IUPAC name.[15]15 Consistency, defined as producing the same output for the same molecule in both representations, was extremely low (often ≤ 1% for many models).

Furthermore, a July 2025 paper by Keyon Vafa, Peter Chang, Ashesh Rambachan, and Sendhil Mullainathan titled What Has a Foundation Model Found? Using Inductive Bias to Probe for World Models generated synthetic datasets to test whether LLMs understood when and how to apply laws of physics. While models occasionally produced correct answers, their reasoning was inconsistent and relied on surface-level patterns rather than internalizing any understanding of the laws.

Other 2025 papers in different technical domains found something similar:

- Large Language Models and Mathematical Reasoning Failures shows how state-of-the-art models (circa Feb 2025) used flawed logic to get correct answers for high-school level word problems.

- A separate paper, Syntactic Blind Spots: How Misalignment Leads to LLMs’ Mathematical Errors, illustrated that some mathematical errors made by LLMs were not always the result of gaps in math knowledge, but due to the brittleness of LLMs’ representations of knowledge. When questions were rephrased in a way that preserved semantic content while reducing complexity, models’ responses improved.

- Finally, Comprehension Without Competence: Architectural Limits of LLMs in Symbolic Computation and Reasoning shows that model understanding revolves around brittle surface-level patterns, even if models innately have reliable representations or associations that could provide deeper context on a topic. The researcher who wrote this paper calls this computational split-brain syndrome. Unlike my dementia metaphor, this points to scenarios where no amount of prompting can help a model recover an association due to architectural limitations.

These studies don’t disprove the existence of world models in narrow domains, but they reveal how ill-defined the concept becomes outside of them. My own view is that what we call a world model may simply be a property of language itself. Language encodes an immense network of relationships that trace the shape of the world. A system trained to internalize those patterns doesn’t so much build a world model as give form to an existing, collective one by making visible the many hidden regularities in how people talk about the world.

As unreliable as LLMs can be, it’s possible we’ll see improvements by fine-tuning models, building trained-for-purpose models with specific tools or coming up with clever engineering hacks. But I suspect that, as some researchers are beginning to say, we’ll have to move away from the transformer architecture to completely avoid this problem. Until then, LLM providers and companies are building scaffolding that makes LLM behavior more reliable, which I’ll talk about below.

The scaffolding of a LLM’s orchestration layer

An oft-cited July 2025 MIT study says 95% of AI pilots fail. The purported 5% of companies that have successful AI pilots have learned that LLM services are actually complex, multipart systems where the model is just one component. Any “intelligence” from these systems does not solely come from the model, but from orchestrating workflows that increase reliability according to specific benchmarks.

I know this isn’t an IT blog, but I’m about to dive into a long list of systems that have to be maintained by entire teams of people. The purpose of doing this is to drive home how much your experience with a LLM is directly influenced by humans making deliberate choices about how a model should behave.

Your eyes might literally glaze over if you’re not a techie, but that’s kind of the point. This is all the human work enthusiasts skip over when they claim their favorite model is a true AGI. Consider each subsystem a unique choice point that shapes the output you get with a LLM, and point to this anytime someone says LLMs are like minds.

A typical chatbot may use the following subsystems:

1. System prompt

System prompts are the prompt effectively “stickied” at the top of every conversation with a LLM. They sit above a user’s prompt and set everything from the tone of a model to what it’s allowed to talk about, and what tools it has access to. They quite literally define a model’s role in an interaction and how to carry that out.

System prompts for frontier models are pretty long because these services are used for so many things. For example, this leaked older version of Claude’s system prompt is 24,000 tokens long and specifies formats and examples for multiple types of queries and hardcodes the fact that Kamala Harris lost the 2024 US election to Donald Trump. Rather amusingly, it also hardcodes that Claude must avoid the tendency to flatter the user at the beginning of a response (ChatGPT tends to start responses this way).[16]16

In many cases, it’s an open question as to what a good system prompt should include, and it partly comes down to the purpose of the system. That’s why there are people employed to A/B test different system prompts. If system prompts are too long, though, they eat into the active context window a model has to process a user’s query.

2. Intention classification and routing

Some LLM setups include systems that try to detect a user’s intent to select the most appropriate model, system prompt, or tool to handle a query. This all happens behind the scenes, invisible to the user, allowing a single interface to leverage multiple specialized models. While routers can improve performance and reduce costs, they can also introduce mistakes or errors, sending requests to a model or system not designed to handle them.

3. “Thinking” models

In the past three years, models that can “think” have been increasingly deployed. In this context, thinking just allows a model to generate tokens behind the scenes, letting it write down a plan of action in response to a prompt before carrying it out. This is one of a few instances when LLMs get to be like the original Leonard Shelby from Memento.

Thinking is useful in procedural tasks to help a LLM break down objectives and stay on target. There is literature on thinking, especially in structured domains like math, that is helpful. But in my experience with smaller local models, thinking results in neurotic and unhinged outputs. Models have to be trained to think well, and it should be strategically leveraged in limited use cases. Toggling between thinking and non-thinking modes is often part of a routed workflow. For example, when GPT-5 displays thinking in its interface, it typically indicates that the system has switched to the thinking version of GPT-5.

4. Guardrails

Sometimes the system prompt isn’t enough to get an LLM to do what you want. Guardrails are like parental controls: They either protect a model or slap it when it’s about to do something stupid.

Intake guardrails

These generally exist to sanitize or even block inputs. This is necessary because LLMs are one giant security attack surface. Genuinely, the best description of LLMs I’ve ever heard comes from François Chollet, a renowned veteran in the machine learning space. He calls LLMs program databases and prompts program queries. Chollet is being somewhat metaphorical when he uses the word program, however, by definition, an LLM’s purpose is to take any arbitrary input (including potentially malicious code) and transform it. If inputs aren’t sanitized, models are vulnerable to adversarial attacks. Intake guardrails might also serve to moderate responses or prime a model to give specific answers. If these fail, then a model could do something like engage in a state-sanctioned hacking campaign.

Response guardrails

Response or output guardrails exist to double-check a model’s response. If you don’t want a model generating copyrighted material, this is how you’d stop it. You might also use such guardrails as a second pair of eyes on formatting errors for formalized output formats (like JSON).

5. Tools

This is kind of a catch-all section. LLMs are given tools to help them carry out tasks. Calculators for math, code interpreters for programming, search engines for current information. Some tools are really niche and only map to a specific task. For example, when Claude played Pokémon Red it was given a way to read the game’s RAM since it couldn’t see like a human child and read menus.

Tools have to be defined in the system prompt, and giving a model too many tools might overwhelm it. Relying on routers or other types of scripting might help a model switch to tools only when needed.

6. Observability

I hope by this point I’ve established that LLMs are closer to IT systems than to emergent minds. Like any good IT system, one needs to be able to monitor activity, both from a security standpoint and a user experience standpoint. Tools, guardrails, routing, and system prompts must be continually A/B tested for reliability and abuse of the system has to be monitored and prevented.

In addition to the orchestration elements outlined above, a typical enterprise LLM setup may include:

1. Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

When you’re deploying AI in a local context, like a business or for personal use, simply using ChatGPT’s or Claude’s API and calling it a day isn’t enough. For the system to be useful, it must either be fine-tuned on your data or be exposed to it in another way.

One common practice for addressing this is called Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG). RAG connects a model to a data store—such as a database, data warehouse, data lake, or object repository—allowing it to ground its responses in that data. You might build a system like this if you have an agent who must take actions or interact with users based on information contained in specific content.

As with pre-training, chunking for RAG is critical. A model cannot process content beyond its context window, so documents must be split into smaller pieces. Poorly chunked content can reduce reliability: the model might miss important context, misinterpret relationships between chunks, or fail to synthesize information across them. Effectively, the quality of RAG depends not just on the data itself but on how engineers choose to present this data to the model.

2. More RAG

RAG is really a catch-all term for a whole family of approaches. Because LLMs retrieve information via statistical similarity as opposed to some abstract notion of “true meaning,” RAG by itself isn’t always sufficient to produce grounded or accurate information. One popular method of modifying RAG is adding metadata to content within the data store to increase its odds of being retrieved by the model at the right time. For example, you might add timestamps to a paragraph of text to change its odds of appearing in time-based queries.

For systems that require a high degree of accuracy, you might have to come up with an entire schema for tagging every single bit of data correctly, and then benchmarking retrieval accuracy continuously. The goal is to throw little consistent breadcrumbs in your RAG data store to get Grandpa Shelby to form the right associations at the right time. This of course requires engineering time and maintenance.

3. Knowledge Graphs just kidding, even more RAG

Knowledge graphs are a special type of data store that explicitly track relationships between entities. For example, if I wanted to build a graph-based system to answer questions about my blog:

- I could store the fact that Mike (entity 1) writes (relationship) Misaligned Markets (entity 2).

- Each blog post could be stored as a chunk, linked to its title and to me as the author.

With this structure, an LLM can be asked, “What did Mike say about X?” and provide a reasonably accurate answer. The model itself doesn’t inherently understand the graph. Instead, it relies on these clear associations to retrieve relevant information. In more complex systems with many entities and relationships, knowledge graphs help disambiguate similar terms and ensure that retrieved chunks are contextually relevant. While my example is simplified, the key point is that providing a model with explicit, structured relationships it does not have knowledge of can substantially improve response accuracy.

4. Layered/Hierarchical RAG frameworks for “continuous memory”

Emerging RAG frameworks are allowing engineers to integrate multiple data stores with a model, so that memory becomes an active part of the model’s conversational context. This has been referred to as “context engineering,” but I prefer to think of it as layered or hierarchical RAG[17]17. RAG is still happening, but a model plays an active role in choosing when and how to use any of the data stores, prompts, and tooling it has access to.

Basically, a model can decide which content is most relevant for the current interaction, while lower-relevance content is relegated to a longer-term store that is not directly in context. This layered structure enables the model to determine what to write to a data store, what to keep in immediate focus, and what can effectively be forgotten. Now we’re really recreating the plot of Memento! Like OG Shelby, the model here is at the center of deciding what is and isn’t immediately in context. Kind of like choosing to look at a particular picture at a specific moment. But these frameworks provide the underlying criteria by which the model determines what should be in context.

5. Model context protocol (MCP)

MCP is an emerging standard that allows developers to wrap any service—a web app, database, or tool—in a formalized interface that a model can interact with directly. Instead of requiring the model to interpret an API on its own, MCP exposes the set of valid actions in a machine-readable format, enabling reliable and structured interaction with external services. In a nutshell, MCP is designed to make services like Google Calendar or coding environments easier for Grandpa Shelby to find his way around.

MCP isn’t a cure-all. Like other tools, MCP definitions live in the system prompt and exist within a model’s context. Additionally, while MCPs help inform a model of what actions it can take within an application or system, this does not prevent it from making mistakes. Anthropic, the creator of MCP, recently wrote a blog post highlighting the limitations of the standard. They actually recommend, in some contexts, just replacing MCP tools with deterministic code, rather than relying on a model’s ability to reliably use MCP correctly.

A lot of AI pilots are finding that they might have to write their own custom MCP logic for systems they need to connect LLMs to. While MCPs aren’t that complex to build, this is still another subsystem that has to be monitored and maintained, which requires engineering time. A non-trival amount of this should be dedicated to security considerations, as MCP allows a model to use services as a privileged user.

LLM’s aren’t useless, but are unreliable without scaffolding and scoping

As you can tell, a lot of work goes into making LLMs reliable. The multiple iterations of RAG illustrate that in order for people to get value out of language models, they need to have data that is structured, clean, and organized in such a way that it’s easily accessible by a model.

Even then, this isn’t a guarantee that LLMs will work or are ideal for the specific use case that someone has in mind. Adding and maintaining all these systems come with tradeoffs, as well. Models only have a limited context window; the more dependencies you add, the more brittle workflows can become.

This tends to mean that models are not so much universal human replacements as they are highly customized tooling. Like all automation, it is possible for LLMs to automate some types of work, while still requiring a lot of work to maintain.

Despite how critical I’ve been about LLMs, I don’t hate them. In fact, I’m a power user. This post mostly attacks the notion that LLMs are intelligences. It’s this idea that’s driving people and companies to interact with models in ways they’re poorly suited for.

So when are LLMs useful? They’re best used in environments where you can control their parameters and have scoped them for a specific use case where you can benchmark their accuracy. For larger use cases, you’ll have to leverage the IT infrastructure I talked about above, like RAG and knowledge graphs, with the understanding that not every system you build will work in production.

Sir, I signed up for Misaligned Markets… What’s all this about?

What does a 6,000-word rant guide on LLMs have to do with political philosophy and economics? In previous blog posts, I’ve alluded to how my experiences as a cybersecurity writer have shaped my understanding of economics. For me, technologies that create affordances for misuse and abuse are evocative of the ways information asymmetry functions within our modern economy.

This means I have no problem doing a deep dive on a technology like LLMs, where confusion disempowers users and encourages economic waste in the form of non-productive uses of a technology. But also, the discourse around language models provides opportunities to talk about economic psychology and bubbles. Consider this blog post the first in a series where I’ll explore these ideas.

- A homelab is basically a local server on one’s home network. This is usually done for the purposes of experimentation or for self-ownership over one’s data. I have a LLM inference server as part of my setup to learn about LLMs.

- Hyperscalers are behaving like GenAI will eventually become a multi-trillion-dollar market by investing hundreds of billions of dollars to realize that outcome. Fears of a bubble are predicated on demand for language models not being anywhere near such a figure.

- For a more in-depth view, 3Blue1Brown has a longer video on transformers, the architecture behind LLMs, here. https://youtu.be/wjZofJX0v4M?si=XdqdoBWdAPAZLFL2

- To understand how large this is, the average word is about 4 to 6 bytes, assuming 1 byte per character and an average word length of 4-6 characters. With a 1TB dataset that's ~250 billion words. Supposedly, way more words than a Brit spoke in a lifetime back in 1983. Datasets are compressed and filtered, though, so most models come closer to ingesting that 1TB number.

- What a subword is can differ between models.

- This is a HUGE simplification, go learn about gradient descent.

- A vector is a point defined by its direction and distance relative to other points within the same space. In language models, those relationships give a point its meaning. Tokens that occur together in text end up close together in this space. Basically imagine a constellation of stars, where tracing lines between specific stars forms recognizable shapes. The geometry of their relationships defines how the space can be traversed.

- Traversing is a metaphor here, as nothing literally moves inside the model. The important idea is that the shape of the space matters. When responding to an input, the model performs calculations that identify which embeddings best fit the current context. While no traversal occurs, it can be useful to imagine these calculations as walks or movements within the model’s vector space as visualized in the 3Blue1Brown YouTube short.

- There are continual pre-training setups where models are regularly enriched with new associations, a process with its own tradeoffs. This is uncommon enough, though, that you can assume most LLMs you'll encounter functionally have anterograde amnesia starting from the moment they finish training.

- For a human mind, it'd be kind of weird to emphasize both the amnesia and dementia; amnesia is usually a symptom of some forms of dementia. In LLMs, though, these definitely are "experienced" as if they were distinct things.

- I wish I could take credit for this Memento analogy, but I didn't come up with it. I think I first encountered it on Mastodon, but a quick Google shows others have connected the same dots.

- Two points: Tokens are contextual, so the same word can be represented with different token values depending on context, effectively codifying variations in language use. Also, yes, I know we've moved on from counting r's in strawberry and on to counting b's in blueberry. While this is an artifact of tokenization, it's worth pointing out that this is how models see the world.

- This notion is captured within a field called distributional semantics. Its founder, John Rupert Firth, captured this idea in the quote: “You shall know a word by the company it keeps.”

- Fine-tuning refers to taking a pre-trained language model and continuing to train it on a smaller, targeted dataset so the model adapts its behavior toward a specific domain or style. Usually, it's an end user who does the fine-tuning. For example, I could fine-tune a local model, like llama-3b on language specific to Misaligned Markets so it could give my specific definitions for phrases like "capitalist serialization."

- SMILES stands for Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System. As an example, the molecule 2-acetyloxybenzoic acid can be represented as CC(=O)OC1=C(C=CC=C1)C(=O)O or 2-acetyloxybenzoic acid (official IUPAC name).

- The newer Claude prompt is slightly shorter with fewer explicit examples. System prompts don't have to be long, but from what I can tell, best practices are being figured out.

- It seems no one is using either of these terms, but they make sense to me. RAG is not going away; people are just trying to exert greater control over when and how retrieval happens. Hence, there's a hierarchy or ranking of information by relevance. Alternatively, you could consider the use of multiple data stores as an attempt to "layer" multiple stacks of RAG.