The tension at the heart of market capitalism

Capitalism promises competition, but its biggest winners avoid it. Separating markets from capitalism explains this paradox.

You’ll often see me use the phrase “market capitalism” to describe capitalism. This is intentional, as my goal is to help us see how companies view the world. Doing so requires an abstract model of the underpinnings of our economic system. Capitalism is ultimately a system intended to track and codify ownership in order to facilitate capital accumulation. The tools we use to accomplish this—laws, as well as political and judicial institutions—ultimately provide a distinct set of profit maximizing opportunities beyond those provided by markets.[1]1

This reveals a deep tension in capitalism: Property rights enable functioning markets, where producers are incentivized to participate as a result of rewards they directly capture when selling things they own (i.e., profit-seeking). However, property rights also restrict where market competition can occur by limiting access to resources or otherwise monopolizing them based on who first accessed them.[2]2 Thus, it will often be desirable for any profit-seeker to use the state to expand the domain of their property rights in order to shield themselves from market competition.

Solving this problem is hard because even if governments were “shrunk down” to just the institutions that enable property rights, it is these very institutions that market actors seek to target, capture, and expand in order to compete.

Markets vs capitalism

Uncritical ideological defenses of capitalism treat the phrase “free market” as perfectly interchangeable with capitalism. The irony, which I’ll elaborate on later, is that markets under capitalism are not unambiguously “free” because the state has to enforce property rights. These rights allow for a guaranteed monopoly of access to processes, ideas, or physical things.

While our legal system is not designed to address the philosophical and moral questions surrounding ownership of abstract things, like ideas, an acknowledgement of the messy nature of creative ownership is baked into the capitalism's legal infrastructure.[3]3 People with the proper means can appeal to the courts—and to the public—that they’re rightly entitled to compensation if they feel they’ve been cheated. This tolerance is an important check against abuse, but it's become increasingly gameable. So much so that, as former Google CEO Eric Schmidt confessed openly and of his own volition, entire industries rely on an army of lawyers to “clean up the mess” that occurs when companies ride legal gray areas around intellectual property (IP) law. This often involves knowingly violating IP to amass the capital needed to win property rights battles in court.

In any case, property rights, even when they aren’t abused, ultimately prevent competition, the mechanism that allows markets to self-regulate. Even if we assume property rights are inalienable and do not require a state to enforce, the belief that whoever is first to access a resource or produce an idea should have a monopoly (however short) functionally limits where and how markets operate, resulting in efficiency tradeoffs.

Herein lies our first clue markets and capitalism aren’t the same thing. To see why, let's evaluate the meaning of each word in the phrase “market capitalism:”

Markets are a means of resource allocation or distribution that relies on buyers who know what they want and sellers who know which things are “worth” producing to satisfy needs. Capitalism, meanwhile, refers to a mode of ownership. Under capitalism, market actors with private interests have the right to borrow or acquire assets, ideas, and resources in order to provide a good or service. This facet of capitalism, often referred to as ownership of the means of production, is not inherently unique to it. What is unique, though, is the extent to which ownership is legally codified within the system. As capitalism has progressed, we’ve seen an increasing number of companies practicing Google's/Eric Schmidt’s playbook, wielding property rights like a weapon to claim ownership of things like words, animals, or even entire genomes, all to prevent competition.

The role of property rights in capitalism

Property rights create a sphere of restricted access to some “thing” in order for its owner(s) to derive income from it. The hope is that income ideally inspires owners to do something productive or additive with their property, which makes them richer and all of us better off. But it doesn't always work out this way—ownership can also be extractive and destructive, where the benefits come from merely hoarding access to something scarce and valuable.

Except in morally unambiguous cases like slavery, it can be difficult to know in advance whether a property right will lead to productive or harmful outcomes. Furthermore, because property rights are distributed, acknowledged, and protected by a state, many capitalists will implicitly converge on the goal of using the state to secure property rights in a way that advantages them (as Eric Schmidt freely shared with us plebeians), even if it’s to the detriment of society.

The case of Labrador Diagnostics provides a brief example that highlights how absurd this can get. During COVID, this company used patents acquired from Theranos[4]4 to prevent competitors from bringing fast-acting DNA-based tests to market. Here we have a company using a patent to block competition, which it acquired from another company that created these patents to hide medical fraud that nearly killed people.

Classical economists, like David Ricardo, distinguished between different types of economic income. Ricardo, building off his predecessor, Adam Smith, coined the term “economic rent” to refer to income derived from hoarding access to a scarce resource as opposed to income gained from wholly productive activity. Property rights provide owners with a dual incentive: to participate in the market to get returns and to avoid market competition where possible. Companies like Labrador are merely following misaligned structural incentives, even if doing so violates our expectations that market actors compete fairly and provide meaningful contributions to society.

The rent (seeking) is too damn high

About 100 years after Ricardo, neoclassical economics revisited the concept of rents, identifying that market actors can “seek” or create opportunities to extract them. This behavior, called “rent-seeking” is somewhat of a contentious concept in economics. The disagreement is not so much about whether rent-seeking exists, but about what behaviors count as rent-seeking, when exactly it should be considered detrimental to society, and if it’s growing (and how much that’s a problem).

Underlying this disagreement are also questions about human preferences and the entitlement of market actors to do what they wish with their property. People who own things are not obligated to use them in ways we approve unless the law compels them. Companies can sell licenses instead of transferring ownership, then revoke access at will.[5]5 Market actors can engage in patent trolling to acquire property rights that make it harder for competitors to produce things. Private equity groups are free to treat hospitals like financial assets as quality of care and patient outcomes worsen. This “enshittification” of society is the natural consequence of capital enabling companies to break free of their obligations to all of us.

While questions about rent-seeking remain unsettled, the 21st century has seen a flurry of controversies around intellectual property, with companies going as far as trying to patent human gene sequences. One major ongoing battleground for this conflict, which you’re likely very familiar with, is the digital sphere. There have been an increasing number of economic, legal, and moral debates around data, digital goods, and digital platforms. In an upcoming post we'll go over these issues in detail, but for now let’s stay high-level and develop a useful conceptual understanding of market capitalism.

Markets and capitalism: a functionally dysfunctional couple

Examples like the ones above illustrate that capitalist competition often takes place outside the so-called “free market.” This isn’t to say firms step outside markets altogether, but that capitalist markets embed firms in a broader environment—where legal maneuvering, information control, and regulatory arbitrage matter as much, if not more than price or productivity. While Econ 101 presents markets as isolated systems, they are instead embedded systems that are part of society and ecology. This means effectively the whole world is a market actor's operating environment.

A lot of people view the perverse incentives of capitalism, like corporate kung foolery, as a straightforward consequence of market incentives. This isn’t exactly wrong, but it’s incomplete, as it doesn’t grapple with the ways that the legal and political regimes that enable private property affect market formation. What we refer to as capitalism is actually a marriage of circumstance between markets and state-enforced property rights. This is why I’m so insistent on referring to capitalism as “market capitalism.”

This metaphorical marriage results in a set of internal paradoxes that have to be addressed by policy and collective action. Unfortunately, these are often resolved in ways that can never fully satisfy market fundamentalists or those of us with a broader conception of human values above and beyond markets. In any case, careful study of the tensions between markets and capitalism can give us a clearer understanding of issues highlighted in this post and others. These tensions are captured in what I've dubbed the “four paradoxes” of capitalism.

The four paradoxes of market capitalism

The purpose of the four paradoxes is to improve collective understanding of political economy by closely examining the systemic contradictions within market capitalism. Each paradox stems from the unique interaction of capitalist legal logic and market forces bumping heads. Two of the paradoxes are predominantly driven through inefficiencies of capitalism, and the other two are driven by inefficiencies created by markets.

Of course capitalism can’t fully be separated from markets, and even paradoxes revolving around market dynamics rely on property rights and legal institutions. Regardless, I think this is a useful exercise to see how markets interact with broader social, legal, and political systems. You can think of the paradoxes as continuums with various types of policies or outcomes existing along a line.[6]6

Paradoxes caused by the “capitalism side” of market capitalism

Learn more about right to repair

- Property rights allow for incentives and compensation to exist in market systems, but property rights inherently restrict where competition occurs, which can undermine market self-regulation and access.

Learn more about patent fences and thickets

Learn more about patent trolling

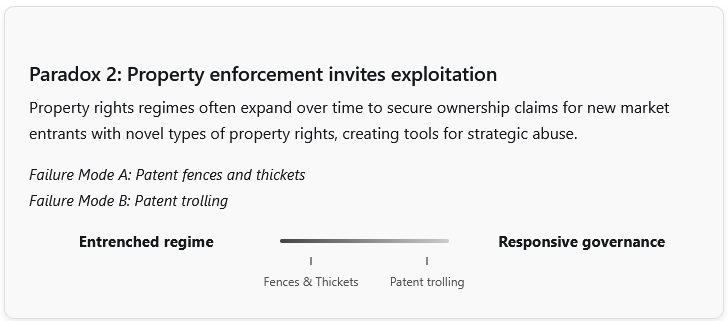

- If the state is too weak, then the cost of violating property rights is relatively low. Thus, the complexity of state-enforced property rights regimes tends to grow as markets mature. This, in turn, creates new opportunities to exploit the state to undermine competition.

Paradoxes caused by the “market side” of market capitalism

Learn more about corporate kung-fu

Learn more about perfect competition

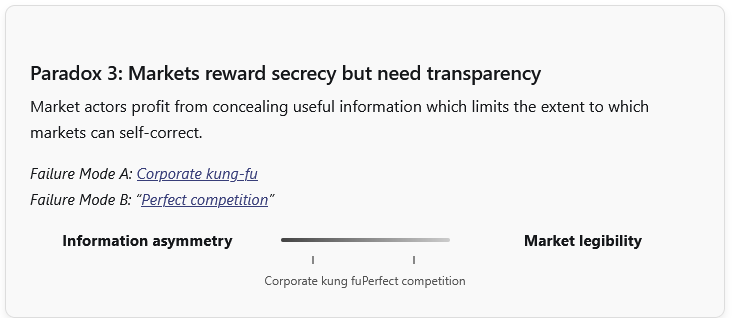

- Information has a tendency to diffuse to where it’s most useful, unless impeded, but markets reward secrecy through property rights.[7]7 The consequence is a strong incentive for market actors to create information asymmetry and a reduced ability for markets to self-correct by identifying and iterating on useful information.

Learn more about Amazon Most Favored Nation clause

Learn more about thin markets

- Markets can create Matthew Effects (“rich get richer” cycles) where the proceeds from winning market competition can be invested in undermining market competition, often by expanding property rights and exploiting the other paradoxes.

There’s a phantom “fifth” paradox, although this simply emerges from the interplay of all the paradoxes:

- All paradoxes of market capitalism are self-reinforcing of themselves and one another. This makes resolving these paradoxes in a way that doesn’t worsen market competition a sort of wicked problem.

What’s special about capitalism’s four “paradoxes”

The four paradoxes map the terrain of market capitalism. Each one is a bundle of tradeoffs that outline the possibility space of outcomes that judicial, legislative, and corporate behavior push us toward. For citizens and policymakers, the paradoxes are intended to help us think through the type of capitalist system we want to create. For firms and other market actors, the paradoxes inform what types of opportunities can be exploited to maximize profits. The ongoing political, social, and legal fights over these paradoxes shapes what type of system we live under. This makes market capitalism a metastable system whose internal configurations are always changing.

Essentially, my four paradoxes are the choices made by society collectively that shape many of the problems that capitalism can create (monopolies, inequality, and overall systemic fragility). The various answers to these paradoxes can help show why capitalism is such a flexible and enduring system—one compatible with everything from chattel slavery to Nordic-style market systems.

Although I’m far from the first to point out that capitalism has fundamental tensions, my scope is narrowly focused on how capitalist societies operationalize capitalist markets. Something like the tension between labor and capital, for example, is downstream of my framework.

I’m also well aware that choices made in response to these paradoxes aren’t made in a vacuum. And unfortunately, some actors have substantial influence over which outcomes are more likely. In future posts, I want to use these paradoxes to understand corporate misbehavior and find ways of navigating market capitalism’s other challenges.

Summary

- Capitalism is better thought of as “market capitalism.”

- Capitalism is a system intended to track and codify ownership of things (property rights) in order to facilitate capital accumulation.

- The tools we use to accomplish this—laws, as well as political and legal institutions—ultimately provide a distinct set of profit-maximizing opportunities beyond those provided by markets. This puts capitalism in tension with “free” markets, though some capitalist systems navigate this tension better than others.

- Markets are a means of resource allocation or distribution that relies on buyers who know what they want and sellers who know which things are “worth” producing to satisfy needs.

- Capitalism is a system intended to track and codify ownership of things (property rights) in order to facilitate capital accumulation.

- As capitalism has progressed we’ve seen more companies wielding property rights like a weapon; offensively expanding the domain of their property rights to limit competition.

- Property rights by design are intended to bypass competition by limiting access to a resource in order to guarantee its owner income.

- There are four tensions or paradoxes that emerge from the relationship between markets and capitalism. The way in which society collectively addresses the tradeoffs posed by these paradoxes shapes the type of capitalism that develops:

- Operationalizing property rights (to enable capitalism) results in the following tradeoffs/paradoxes:

- 1. Property rights allow for incentives and compensation to exist in market systems, but property rights inherently restrict where competition occurs, which can undermine market competition.

- Operationalizing property rights (to enable capitalism) results in the following tradeoffs/paradoxes:

- 2. If the state is too weak, then the cost of violating property rights is relatively low. Thus, the complexity of state-enforced property rights regimes tends to grow as markets mature and transactions depend on more sophisticated property rights. This, in turn, creates new opportunities to exploit property rights to undermine competition.

- Operationalizing markets results in the following tradeoffs/paradoxes:

- 3. Information has a tendency to diffuse to where it’s most useful, unless impeded, but markets reward secrecy through property rights. The consequence is a strong incentive for market actors to create information asymmetry and a reduced ability for markets to self-correct by identifying and iterating on useful information.

- 4. Markets can create Matthew Effects (“rich get richer” cycles) where the proceeds from winning market competition can be invested in undermining market competition, often by expanding property rights and exploiting the other paradoxes.

- All paradoxes of market capitalism are self-reinforcing of themselves and one another. This makes resolving these paradoxes in a way that doesn’t worsen competition a sort of wicked problem.

Recommended resources

How capitalism is constructed

- Book: The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality by Katharina Pistor

- Book: Marketcraft: How Governments Make Markets Work by Steven K. Vogel

- The Great Transformation The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time by Karl Polanyi

- Book: Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society by Eric A. Posner and Eric Glen Weyl

Markets, manipulation, and info asymmetry

- Book: Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller

- Book: Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Climate Change by Erik M. Conway and Naomi Oreskes

- Book: Lying for Money: How Legendary Frauds Reveal the Workings of the World by Dan Davies

Capitalists hate competition

- Book: Saving Capitalism From the Capitalists by Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales

- Book: A Hacker's Mind: How the Powerful Bend Society's Rules, and How to Bend Them Back by Bruce Schneier

- Article/Video: Competition is for Losers (Wall Street Journal, Y Combinator) Peter Thiel[8]8

Affiliate disclaimer

Books on this page and throughout the site link to my Bookshop.org affiliate pages, where your purchase will earn me a commission that will go towards covering site costs. If you at all find the books I recommend interesting, consider purchasing through Bookshop, which shares profits with local bookstores. You can learn more about how you can support Misaligned Markets here.

- Some neoliberal thinkers might view my argument as incoherent, since they see markets and property rights as co-constitutive. I disagree: even minimal state-enforced property rights introduce distortions worth making explicit. It's better to highlight this tension so we can do political economy with informed tradoffs.

- I’m not saying that this is inherently undesirable. The point is that markets under capitalism can effectively be thought of as a type of institution that requires specific kinds of tradeoffs to operationalize or make function. Market capitalism doesn't just emerge spontaneously, and there are better and worse versions of it.

- While we typically attribute inventions of technologies or concepts to one person, most ideas are iterative, they come from existing things in the world. It’s also possible for two or more people to independently come up with the same thing. Regardless, the state must play the role of an adjudicator to decide in such instances who “deserves” rewards for something, and it can often get this wrong.

- Yes, that Theranos.

- As I'm writing this, the EU petition "Stop Killing Games" is gaining traction. Games like other media are increasingly sold with revocable licneses. But this is far from the only industry where this is happening.

- This is a huge simplification. These paradoxes are multidimensional, and I'm still working out how to represent them. For now, a 2D line including hypothetical examples of outcomes is meant to simplify the representation of the tension just to illustrate the basic concept.

- Originally this was: “Information wants to be free (IWTBF), but markets reward secrecy.” I’m avoiding IWTBF because it’s not a neutral language. But taken literally, I think Stewart Brand was simply trying to provide a descriptive assessment of how information circulates in relatively open societies

- My recommendations should not be seen as explicit endorsements. They’re just things that I’ve encountered that are relevant to the topic at hand. This disclaimer is especially true of Thiel. Like Eric Schmidt, Thiel is an anticompetitive monopolist (with strong anti-democratic opinions) who has openly given up the game, so to speak.