The historical contingencies of Anglo-capitalism

Capitalism is a social technology and a system of governance predicated on specific historical developments.

What exactly is capitalism? One thing that makes capitalism hard to talk about is that, as an abstract term, it doesn’t have a single referent. Let's disambiguate the term so we can have more productive discussions.

Disambiguating capitalism

Many systems in the world are capitalist, each with a variety of distinct features:

- Japanese capitalism in the pre-WWII era was defined by extreme concentration of wealth and market power held by families in control of vast vertical monopolies, colloquially referred to as the “Zaibatsu.” That’s why, to this day, some Japanese companies’ names are simply surnames, with their histories dating back to just after the Meiji Restoration (e.g., Mitsubishi).

- Modern Norway is defined by strong labor protections and an expansive social safety net that’s partially funded by a state-owned oil company.

- The US in the antebellum era (early to mid 1800s), late 1800s (Gilded Age), 1930s (post-Great Depression), and 2010s (post-Great Recession) might as well be different worlds, despite all being instances of American capitalism.

Interestingly, the wide variety of capitalisms provides something of a natural experiment. If occurrences like inequality and market concentration consistently appear across capitalist systems, each with a different role for the state, this might identify something fundamental to the construct. For example, Zaibatsu Japan and the US Gilded Era are ages of capitalism with high inequality, with the former culminating in World War II and the latter in the Wall Street Putsch, a plot that implicated the wealthiest Americans. Despite the differences across societies, there are genuine questions this invites about eras like our current one, which is similarly defined by nearly identical levels of inequality and elite political influence.[1]1

Outside of examples like these, there are competing conceptualizations of capitalism, as it’s an essentially contested concept.[2]2 While there are specific defining features common to all instances of capitalism, mainly private ownership enforced by a state, discussions about the nature of capitalism often devolve into debates over its ideal type.[3]3 One such question, for example, is whether capitalism is inherently defined by freedom of exchange (whatever that means) or exploitation (whatever that may mean). I find discussions like this unproductive, even though I have opinions about them. In this post, I want to focus on the social, legal, political, and economic practices that were essential to the formation of modern capitalism in Anglosphere countries, though I may return to the discussion of ideal types in a future post.

The components of modern US-style capitalism

Popular discourse about capitalism often obscures the dependencies required to run a functioning capitalist society. People often say things like, “Capitalism is just buying and selling stuff.” This isn’t just wrong because it's shoddy history; it’s also wrong because it uses anachronistic thinking to erase humanity’s rich cultural diversity to make the past feel more familiar. Unfortunately, it’s easy to fall into this way of thinking. There’s no shortage of material, even from very thoughtful thinkers, which justifies this view.[4]4

This isn’t to reject the idea that parts of modern capitalism haven’t appeared throughout human history; they definitely have. What makes modern capitalism distinct is the specific combination of legal, financial, economic, and governance practices that have come together to create the modern corporation. To reduce capitalism to “exchange” is to miss the importance of the collective synergies enabled in the capitalist world of today. It also hides the substantial difference in power that modern market actors, like multinational corporations, have when compared to actors in earlier markets.

The task of defining modern capitalism and the particular developments that made it possible has filled entire books. There’s no way I can do this justice in a single blog post, so we’ll undoubtedly talk about it more in future posts. For now, let’s take a brief tour of eight of the most important developments critical to capitalism as it exists today in anglophone countries—specifically the US and UK.[5]5 These developments are core to illustrating what the “technology stack” of capitalism as a system of governance looks like.

1. Property rights

For the sake of time, I want to avoid engaging in any deep history, ontology, or moral philosophy of property rights. These are, sadly, topics I’ll have to save for yet another post. For now, when I use the term “property rights,” I’m specifically referring to those recognized and enforced by a state. Any other kinds of property rights would not be sufficient for the vast amounts of investment, trade, and accumulation enabled by modern capitalism for several reasons:

1. Nation states have enabled global trade by opening up access to new markets (through imperial violence or diplomacy) then ensuring the property rights of their citizens are as respected abroad as they are within the nation’s borders. This is one key reason the United States, for example, patrols the seas to enforce maritime laws for its allies and coordinates with other countries to punish actors in other markets who violate US copyrights. Everything from pirates stealing cargo to foreign knockoffs reduces profits, and the state plays a huge role in limiting this while expanding access to these markets.[6]6

2. As the complexity of things bought and sold in the economy has grown, the property rights needed to manage them have grown as well. Nation states help reduce this transaction cost by keeping property records and maintaining courts for property disputes. This is all to ensure property owners can properly reap their rewards by providing recourse if markets should fail to respect rights of ownership.

3. In nation states where property owners have strong representation in government—either directly as members, via representatives, or via proxies (like lobbyists)—they can ensure that property rights for new markets, or emerging markets with poorly defined rights, are interpreted in ways that don’t disrupt their business or even allow them to expand their business. We’ll talk more about this below in the section on representative democracy.

2. Commodification

Commodification is the ability to turn some physical or abstract thing into a commodity—something that can be traded or bought and sold. Commodification is as old as commerce. It often requires well-defined property rights of the kind I stated above. But sometimes exchange and, thus, commodification can occur without property rights. In fact, some views of commodification argue that there’s fundamentally no limit to what can be bought and sold, as it’s human desire that forms the basis for market creation.[7]7 Even the state’s legal boundaries cannot completely stop the formation of black markets, although here, only possession and not property rights exist. However, many market actors understand the value of having sanctioned property right protections, which is partly why states expand to defend even controversial notions of property. Still, while there’s no limit to what can be commodified, legal and social norms play a huge role in enabling markets with extensive legal property protections.

Weak property rights also drive capitalism. Market actors are always in pursuit of ever and ever more growth; thus, they’ve often got an eye out for opportunities where weak property rights enforcement can create new opportunities. Tech provides ample examples of this. As I’m writing these very words, Google and OpenAI are arguing that they need to violate publishers’ copyright to build functional AI products. It’s an open question whether high-valuation AI companies can use their new advantageous position to bypass the need to license the massive corpus their machines are trained on. Should they accomplish this, they’ll have successfully built a commodity off torrented works.

Other growing areas of tension include data ownership more broadly. In an earlier post, I shared a story about General Motors (GM) selling the de-identified driving data of individuals who purchased their cars. This invites questions about data ownership: Does the data belong to GM, who built the telemetry and the car? Or does that data belong to the owner of the car who purchased it? Or maybe it belongs to no one? Is data even something that can be meaningfully “owned” by anyone? Capitalism doesn’t inherently give us an answer; all we have are the contracts that users implicitly “agree” to when making a purchase and, if we’re lucky, legal and legislative precedent.[8]8 But in the absence of clear precedent, companies are free to use any wealth they’ve accumulated to nudge the legal and political system in ways that resolve disputes in their favor. See my post on the four paradoxes of capitalism to understand aspects of this process. In future posts, we’ll talk more about business models that specifically capitalize on asymmetric copyright enforcement and “contested” commodities like data, DNA, and others.

3. Financialization

The word “financialization” has a somewhat specific meaning in modern economics. However, here I want to use it to refer to the growth of practices across history that facilitated the expansion of commerce—especially in circumstances where it wouldn’t have otherwise taken place. Credit, for example, removed the need to have capital up front for a purchase or investment, facilitating “just-in-time” transactions for borrowers. Financial practices can generally, though not always, be seen as processes that untether capital from its current time, place, and form. If that sounds like magic, well, it kind of is. Finance leverages legal and economic practices as well as “rational expectations” to create psychological incentives to pool together money. Here’s political economist Blair Fix talking about “the ritual of capitalization,” one of the starting points for financialization. As Fix indicates, capitalization is ultimately just the practice of generating a number, much like an invocation, in order to give value to an asset and turn it into capital so that it can be traded or sold.

The ability to separate the value of capital—an asset or thing with value (or with the potential to accrue value)—from the thing underpinning that value is crucial to how capitalism works, as it’s what accelerates capital accumulation. Think about something like a home equity line of credit (HELOC). A HELOC allows you to take some of the value from a home and put it elsewhere, hopefully somewhere where it’ll accrue more value. Financial institutions operate on the same principle at larger scales: banks bundle individual debts like mortgages into securities that can be packaged, sold, and traded. Companies do something similar through initial public offerings (IPOs), transforming the productive capacity of an enterprise into bundles of tradable claims on future profits.

Finance allows groups of people, many of whom might not know each other, to coordinate across time and space with the expectation that each person in the interaction benefits. Financialization is critical to the velocity of capitalism as we experience it today, allowing both consumption and investment to grow quickly[9]9 Market exchange is no longer limited to capital and cash that companies and people have on hand, which means more market activity can happen, increasing the pace of capitalist growth. Of course, financialization is not some neutral process; those of us who lived through the Great Recession know that finance can be used as a “dark magic” that advantages some over others. Everything I’ve discussed on this blog about information asymmetry and corporate kung fu goes doubly for the world of finance, where bubbles and great destruction can follow from the misalignment of incentives and information. See my discussion of the metaphor of capitalist serialization for an illustration of how finance can be weaponized.

4. Structured liability and contracts

The ability to split and transfer ownership rights and diffuse risk is of great importance to business, which is why people have been doing it for a long time. Collateralization allows the “magic” of financialization, which I described above, to take place. Collateral, usually structured within the context of a contract, builds the initial trust needed to entice investors to participate in finance. Should the chain of decoupled value moving from entity to entity break apart, someone can recoup the original assets that underpinned the interaction.

5. Capital accumulation (investment-reinvestment with positive feedback loops)

The Early Modern Era (about 1500–1800) saw the growth of new types of financial practices and legal infrastructure for market actors, leading to opportunities for capital accumulation (and thus wealth concentration) on a scale never seen. This is when the world’s first global corporations stepped onto the stage, like the British East India Company (EIC) and Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), better known as the Dutch East India Company. These two joint-stock companies are the earliest examples of both imperialism and capital accumulation at scale. While both companies were sanctioned and chartered by their respective states, granting them powers we today associate with governments (like the ability to wage war), they were also financed by pools of investors. Profits from ventures were then reinvested to finance other ventures that would unlock access to new markets, which led to new ventures and so on and so forth.

Capital accumulation is the perpetual motion machine that drives capitalism towards the ever-expanding horizon of infinite growth. This tendency, though, is sometimes at odds with functional markets, as it can lead to monopolization. Essentially, firms with more capital and first-mover advantages can use their capital to lock out competition. Simply having more capital does not guarantee market control, but it makes it more likely. This is why concentration is a common feature among different implementations of capitalism across cultures and eras. But even when capital is not being wielded defensively against market competition, it can blunt many of the self-regulating features of markets. Consider this funny yet depressing Axios article warning normal people against investing like billionaires:

“Billionaires don't need to maximize their returns when they make investments — and they almost never need to sell anything. They're therefore terrible role models when it comes to most people's personal investment decisions. … One of the greatest luxuries that being very rich buys is being able to lose a lot of money and still live a billionaire's lifestyle.”

One of the extolled virtues of markets is that they punish bad actors and bad ideas because, through competition and consumption, these get crowded out. People, generally speaking, don’t get paid for having ideas the market doesn’t like, and in the absence of rewards, actors with bad or malicious ideas will disappear as they run out of money. However, if there’s a class of entity or person who is literally “too big” to lose access to the market, regardless of how perversely they use their wealth, they are effectively immune to the market’s mechanisms of “self-regulation.”

While capital accumulation has financed the growth of socially and economically productive firms that have done good for the world, it can arguably be viewed as a double-edged sword. That's because it also creates the escape velocity needed to avoid the constraining power of markets and governments alike, even if not every instance of capital accumulation results in having such power.

6. Representative democracy (for and by property owners)

When Thomas Jefferson wrote the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence, it was widely understood that he was borrowing from English political philosopher John Locke (1632-1704), who argued that natural rights include “life, liberty, and property.” While there’s debate about what Jefferson meant—whether the pursuit of happiness is distinct from pursuit of property—what is undeniable is that the United States at its founding was a representative democracy for and by white property owners. The history of the US can be seen as the gradual, and often painful, amending of this decision in order to build a democracy that’s actually representative of all its peoples.

The US is not the first representative democracy that granted power to property owners, but it arguably marked a turning point in history where broad swaths of property owners, and not just a narrow piece of aristocracy, were represented. This allowed for a government that could explicitly make decisions that would grow the types of commerce property owners participated in, which was critical to the growth of slavery and, eventually, capitalism.

Along with land, slaves are among the oldest types of commodities in the world. Other than the abject moral deficiency of owning another human being, functionally, slaves were like any other commodity. Many proponents of capitalism reject recognizing slavery as part of capitalism’s history or argue that the use of the state by slave owners is not part of capitalism. I don’t think either is warranted. States don’t create property rights arbitrarily. They’re guided to do so by virtue of representing or being led by property owners who create legitimate markets around their business interests. This makes capitalism compatible with any number of property rights, including ones we find morally abhorrent, inefficient, or in any way problematic. If we’re interested in uncovering the mechanisms of capitalism, our job isn’t to play cheerleader for some ideal type of capitalism, but to actually evaluate the ways in which property rights have been used in capitalist arrangements. This malleability of property rights, in fact, points to a very important quality of capitalist systems and to why capitalism continues to evolve and endure as a system.

Anyway, even if one is sympathetic to some natural rights conception of property rights, every known implementation of property rights requires a complex state that can codify ownership of assets and crystallize the boundaries of what types of things can be owned and, thus, what can be commodified, so ownership can be defended. If the state is too weak, then the cost of violating property rights is relatively low, economically speaking. This doesn’t necessarily even entail defense of property, although it often does.

Keeping track of ownership requires detailed record-keeping and the ability to adjudicate property disputes, which states provide to property owners in representative democracies. Over time, this can cause property owners to become powerful enough to extend property rights to an increasing number of tangible and intangible things, some of which had no prior conception of being a commodity (see here and here for fun examples). This process tends to violate social norms and sometimes disadvantages some groups, but I think it’s an important part of understanding capitalism. Indeed, the drive to find new sources of growth creates political and economic incentives to create new types of property rights and commodities.

Beyond the ability to give “teeth” to property rights, states serve to propagate the social effect—the norms, customs, and beliefs—that normalize acceptance of specific types of property rights by all members of society, including those who might be dispossessed or disadvantaged by the enforcement of specific property rights. This almost always occurs as a political process that shapes the social and legal norms around ownership of a specific type of asset. Indentureship and, soon after, slavery were enabled by men with specific economic interests. They then leveraged the state to codify these laws and helped normalize the conditions that enabled the existence of this commodity. Some slave codes, for example, compelled the involvement of non-slave owners in retrieving slaves.

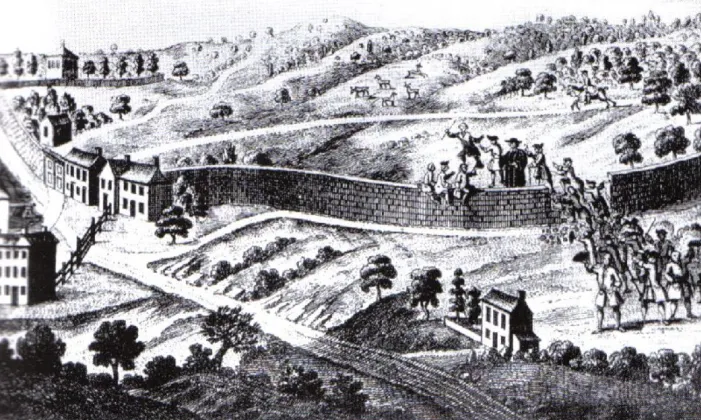

As the US was building its first institutions, across the pond in Britain, landowners were engaged in their own commodification project, the British Enclosure Movement. Enclosure was a gradual, centuries-long process that involved elites altering laws around the use of land by leveraging the power of the state to violently restrict access to lands that were previously considered common or public land. Over time, this enabled land to take on a form more amenable to capitalist logics, though modern economists argue this more efficient use of land greatly increased agricultural yields, which fed more mouths.

Regardless of what good or bad came from it, this was far from a neutral and apolitical process that happened spontaneously without the input of the state. The state, representing property owners, created property rights that protected these interests while violating existing norms and the interests of commoners. Communal farmers no longer able to support themselves were forced to go work for the very same people who had deprived them of their self-sufficiency. The government then played a role in getting these individuals to accept this new state of affairs. This lost self-sufficiency was critical in driving the demand for the grueling, dangerous work that would contribute to the productivity gains seen during the Industrial Revolution.

Today, while we no longer fight over common land and slaves, we still face bitter battles over what can be commodified. Understanding this struggle is critical to navigating some challenges we face this century, as a handful of digital platforms own the infrastructure where we work and socialize.

7. Timekeeping and abstract value

It’s well known among both historians and anthropologists that modern capitalism, as we experience it today, requires mechanical clocks. For much of human history, time wasn’t something that universally bound all humans to a shared, uniform perpetuity. Instead, it served more narrow purposes, like keeping track of seasons for farming, religious ceremonies, or navigation. When time was structured, it was local and for a specific purpose. Many things we now tie closely to clock time, such as hourly wages, are relatively modern. Historically, pay was often by task or quota, and even when workers were paid by the day, the length and value of a ‘day’ varied with the seasons and local custom.

Oddly enough, this alone did little to change the relationship humans have had with labor since prehistory. In many cases, people’s relationship to work was mediated through their natural circadian rhythm and other ambient conditions, like season, weather, and temperature. These natural forces were so powerful that their effect on work patterns still held well into the 14th and 15th centuries within parts of Europe.

It was the adoption of clocks by Europeans that would slowly create a culture that valued abstract time above all else. Originally, clocks and clock bells were used to signify times of worship; however, this would change as clocks became more portable and ubiquitous. Labor was among the first areas reshaped by the spread of clocks. In certain trades and urban centers by the 17th century—and far more widely during the Industrial Revolution—employers began using clock time as a disciplinary tool, petitioning governments to fine tardiness and imposing stricter schedules. Clock bells, which once signified worship, were imported to factory floors to manage employees and keep them on task.

The goal of this emerging capitalist logic was to increase the regularity and output of production, unconstrained by human biology or other considerations. Regularity allows for predictability, which makes coordination with distributors and other groups in a supply chain much easier. More output, of course, means more profit. Modern corporations have tried to swap carrot with stick, but this philosophy has never truly gone away, with even salaried employees facing contemporary forms of labor surveillance.

The tethering of labor to the clock effectively commodified time. Employers were no longer purchasing completed projects, or a designated quota of goods; they were buying the very time of the people they employed, and thus, they felt entitled to get as much value out of that time as possible. Together with other developments like enclosure, this helped create a system of interdependence in which compliance with clock time became increasingly necessary, pressuring people to devote more of their lives to economic concerns—sometimes with negative consequences for health and well-being.

Workers have fought and died for better working conditions and more humane schedules. The 40-hour workweek was a hard-won 20th-century compromise after over 70 years of labor activism. But even these victories have left the basic structure intact: capital accumulation remains the only durable escape. Wealth affords the ability to reclaim a life aligned to one's circadian rhythm by commanding the time of those who lack enough capital to free themselves from this cycle. In this world, hustling, even if only performatively, is seen as a badge of honor.

8. Market societies

The last aspect that’s defining our current moment is that modern capitalist societies are market societies. This term is a little ambiguous, but in most of its uses, it refers to societies where nearly all social and political relations are subjected to market logic.

Just like with land, time, and work, the market has gone on to dominate most aspects of human life. There aren’t very many activities you can do anymore that aren’t monetized. I’ll again point to the GM car telemetry story. Car manufacturers almost successfully turned the activity of driving a car (the very one you’ve already given them money for), into an activity that makes them money at your expense. But even activities you do at your leisure, like watching funny cat videos online, have become part of a market centered around surveillance and ads.

None of these developments is inherently bad, but as Aristotle articulated a long time ago, the mindless pursuit of profit-seeking can dislodge activities from their intended purpose, turning them into something perverse. In these cases, we have algorithms being used to disadvantage people by sharing inaccurate inferences about their driving habits or to push them towards more emotionally and politically polarizing content for the sake of engagement.

A more important feature of market societies is that their mandated role for the government is mostly to increase economic growth and little else. This conception of economic growth tends to be centered on things like GDP, labor force participation, and unemployment, while balancing these against variables that affect business investment, such as interest rates. Concrete policies might revolve around increasing trade or subsidizing businesses to encourage investment. It’s not that government policy is reducible to these objectives, but they are the primary preoccupation of modern governments like the United States. Insofar as we can solve issues that will cause a great deal of harm, like climate change, they must first be reduced to logics that markets can process. Think carbon credits, cap and trade, subsidies, liabilities, etc.

I want to make it clear, again, that this isn’t inherently bad, but allowing market considerations in some domains to crowd out other considerations comes with tradeoffs and can lead to various types of mal-optimizations. One core issue is that neither markets nor capitalism values lives, meaning that the cost of deferred climate action, a consideration made by the oil lobby over 70 years ago, will have unequal impacts on different populations. The broader implication is that this makes market societies uniquely slow to address problems like inequality, which, when left unchecked, can result in deleterious effects on societies. Market societies may in fact barrel headfirst into problems that exacerbate inequality and thus undermine their own long-term stability.

While we should be very wary of simplistic economic anxiety arguments for the rise of leaders like Trump, there is evidence that economic conditions under globalization have contributed to the erosion of jobs and safety nets that have amplified cultural grievances. This is much in the same way that a drought can amplify the risk of fire in a region littered with dry brush.[10]10 Policies like globalization present tradeoffs, which ultimately produce “losers” from capitalism’s perspective—people for whom the system can do without because they aren’t “essential” in the distribution of society’s current “resource allocation.” The consequences of balancing these tradeoffs are important—not just morally, but even from the perspective of narrow self-interest, given how they’ll impact the long-term stability of society.[11]11 Unfortunately, market societies shape the way we approach problems, making imagining solutions beyond market-oriented ones less feasible. In future posts, I want to talk about pluralist values that can play a role in addressing such tradeoffs.

Summary

- Capitalism refers to multiple things:

- Specific capitalist societies that have existed or currently exist in the world. For example:

- Japanese Capitalism between the Meiji Restoration and World War II (1868 to 1946)

- Nordic Capitalism

- The US in various eras:

- Gilded Age (1865-1902)

- post-Great Depression

- post-Great Recession

- An essentially contested concept whose ideal type or core fundamental aspects are in contention in popular discourse.

- Specific capitalist societies that have existed or currently exist in the world. For example:

- In order to understand commonalities across different capitalist societies and features of our modern economy, it’s important to look at historical developments that led to capitalism:

- Property rights, specifically those granted by a robust nation state able to provide resources for property disputes and enforcement of property protections nationally and abroad.

- Commodification

- Financialization

- Structured liability and contracts

- Capital accumulation

- Representative democracy, where property owners have substantive rights and representation

- Timekeeping and abstract value

- Market societies

Recommended reading

Globalization and its trade-offs

- Book: The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy by Dani Rodrik

- Article: Globalization’s Wrong Turn And How It Hurt America by Dani Rodrik

- Video lecture: Karl Polyani and Globalization's Wrong Turn by Dani Rodrik

What are market societies?

- Book: What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets by Michael Sandel

- Book: The Great Transformation by Karl Polanyi

What is finance?

- Book: Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible by William N. Goetzmann

- Book: The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets by William N. Goetzmann, K. Geert Rouwenhorst

Historical contingencies of capitalism

- Book: The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View by Ellen Meiksins Wood

- Book: Slavery's Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development

- Book: Pocket Piketty: A Handy Guide to “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” by Jesper Roine

Timekeeping and labor

Affiliate disclaimer

Books on this page and throughout the site are linked to my Bookshop.org affiliate pages, where your purchase will earn me a commission that will help cover site costs. If you find the books I recommend at all interesting, consider purchasing through Bookshop, which shares profits with local bookstores. You can learn more about how you can support Misaligned Markets here.

- Elite political influence is hard to quantify, as it can be operationalized and measured in a lot of different ways. I don’t have a particular theory I favor, as I’m still learning about this subject.

- Essentially contested concepts (ECS) are abstract things like “justice” or “love” that have multiple overlapping depictions, which are sometimes competing and/or complementary. I’m making an argument when I suggest that capitalism can be considered an ECS. Not everyone would agree with me. Also, not every use of capitalism is an ECS. For example, above, I referred to specific capitalist systems that historically existed.

- An ideal type is a way of thinking about an abstract thing, like a social system, and boiling it down to its most fundamental parts. When we fight over what capitalism is, in my mind, we’re debating about the features essential to capitalism.

- I consider Adam Smith to be among these, though he’s been made an ideological mouthpiece for capitalism over the centuries despite his nuanced writing. In this line, I’m specifically referring to Smith’s "truck barter trade" quote. Barter economies weren’t necessarily the default before money. Of course, Smith writing in the 18th century didn’t have access to the latest anthropological research.

- This is a list of developments that I personally came to after reflection. I absolutely encourage you to do your own historical research and reflection to make additions/subtractions from this list.

- As the Trump admin de-globalizes trade the irony about what the US has done in the past and what it’s doing now isn’t lost on me. But the degree to which Trump policy (or authoritarian, kleptocratic, and fascist policy) diverges from the interests of capital is its own future topic.

- See the book Markets without Limits for an example of such arguments. The authors make a normative claim about how we should think about commodification that can best be summarized as “if you can do it for free you can sell it.” I suspect this normative position is one rooted in their observation of how they believe markets form. I don’t endorse their normative claim, but I do think they might be right about market formation.

- The state of Texas has sued GM over this, and the company has now killed this program.

- Capitalism’s growth requires movement of capital at an increasing pace, and so an increasing percent of our economic progress is being fueled by credit expansion. You’re likely familiar with the rise of buy-now-pay-later firms in every area of the economy. But even business investment cycles are starting to revolve around credit expansion. For at least the last four decades, companies have increasingly begun borrowing money to buy back their own stocks, for example.

- My view of hustle culture is that it’s a signal that shows you’ll one day have enough wealth to be free or that you’ve found a way to reclaim your time by working for yourself, presumably doing what you love.

- For a deeper elaboration of these ideas, see Dani Rodrik’s writings. Rodrik warned about the risk from unmitigated globalization as early as the 90s and has framed globalization as a set of tradeoffs (a trilemma to be specific). See recommended resources below to learn more.