Capitalism runs like a computer (and it's being hacked)

Like computer networks, market capitalism rewards actors that exploit gaps created by system and user behavior.

Recently, we discussed how markets and capitalism function as separate but deeply intertwined layers of market capitalism. This is an abstraction, but one that’s extremely useful for functional analysis of how capital accumulation and profit incentives work in market capitalism. Let’s extend this abstraction by talking about computer networks.

What cybersecurity taught me about economic power

It’s safe to call Misaligned Markets a blog about information asymmetry, with the concept appearing in over half my posts. That’s because markets revolve around this asymmetry; sellers and producers inherently know more about what it is they’re offering.

This isn’t inherently bad. Earlier this year I supported the JetKVM Kickstarter. Devices like this are typically sold to businesses and can be prohibitively expensive for hobbyists like myself. Up until now, the most affordable way to get a KVM was to build one yourself using a single board computer. I was more than happy to support the (two-person?) team that used their knowledge to source and distribute a KVM for a fraction of the cost I was expecting to pay. When market capitalism works, it allows for information to diffuse to where it can become useful to produce the products and services we need in our lives.

Unfortunately, not all people play by the rules. Like hackers, some market actors look for loopholes to find easier ways of making a profit. The market is perfectly happy rewarding profit-maximizing knowledge that solely advantages one party over another. Misleading advertising, dark patterns, personalized pricing, or simply using one’s position to manufacture high switching costs are extremely profitable and shape consumer behavior in subtle but powerful ways.

For most of my career, I’ve been a cybersecurity writer. In 2016, a little more than a year into my career, I realized that the stories I was covering conceptually resembled market failures. The link was information asymmetry. This was the moment that I realized many market failures were the result of companies exploiting vulnerabilities in both people and the rules of market capitalism.

How hacking works

Contrary to popular belief, hacking doesn’t require a computer science degree or any intimate knowledge of computers. Fundamentally, at its core, hacking just requires the ability to create and exploit information asymmetry by abusing gaps in how systems and people behave. A hacker gains access to systems by exploiting human psychology (via social engineering) and sometimes by identifying structural limitations in computer applications or hardware.

The simplest tricks work best. If you want quick cash, hijacking a victim’s bank account will always be easier than breaking directly into a bank’s servers. So a hacker would rather phish you than ever touch a line of code or break into a network. They’ll pretend to be tech support and lure you to a website that almost looks like your bank’s so you can reveal your password.

Knowing how to program and how computers work reveals gaps others might not see, like zero-day exploits. These are structural bugs so deep in applications or hardware that not even their creators know they exist. Extremely skilled hackers can trick a computer into misbehaving without exploits using malware, which turns the very logic of a computer system against itself. But these aren’t tools of first resort for most hackers.

Regardless of approach, the one thing all hacks have in common is that they exploit a gap between rules governing computer systems and how these rules are actually enforced. This isn’t that different from what misbehaving market actors do.

Capitalism as technology infrastructure

As I’ve argued elsewhere, capitalism should be seen as an economic layer distinct from markets, if only for analytical purposes.

Similar to hackers who know how to read code, market actors with an understanding of how capitalism works can exploit gaps others can’t see. They weaponize law and political bodies, the very infrastructure that enables market capitalism to function, to collude, punish consumers, and stifle competitors.

I’m not the first person to relate cybersecurity and capitalism. Economists Robert Shiller and George Akerlof, both foundational to the concept of information asymmetry in markets, wrote a book literally titled Phishing for Phools.[1]1 Bruce Schneier, a veteran well-known in computer security, provided his own take in A Hacker’s Mind. In it, he explores how powerful actors routinely exploit systemic legal and financial rules to their own advantage. This is why it can be useful to think of capitalism like a technology stack. Market abuses don’t simply emerge at the level of prices and consumer preferences; many instead originate deep within capitalism’s infrastructure.

What is a technology stack?

When troubleshooting or building IT systems, it’s useful to break them into layers or modules that model how subsystems interact. This helps us reason about everything from how a website functions to the underlying protocols letting you connect to it. At its simplest, a tech stack is just a description of the technologies that make up a working system with each layer of the stack handling specific responsibilities.

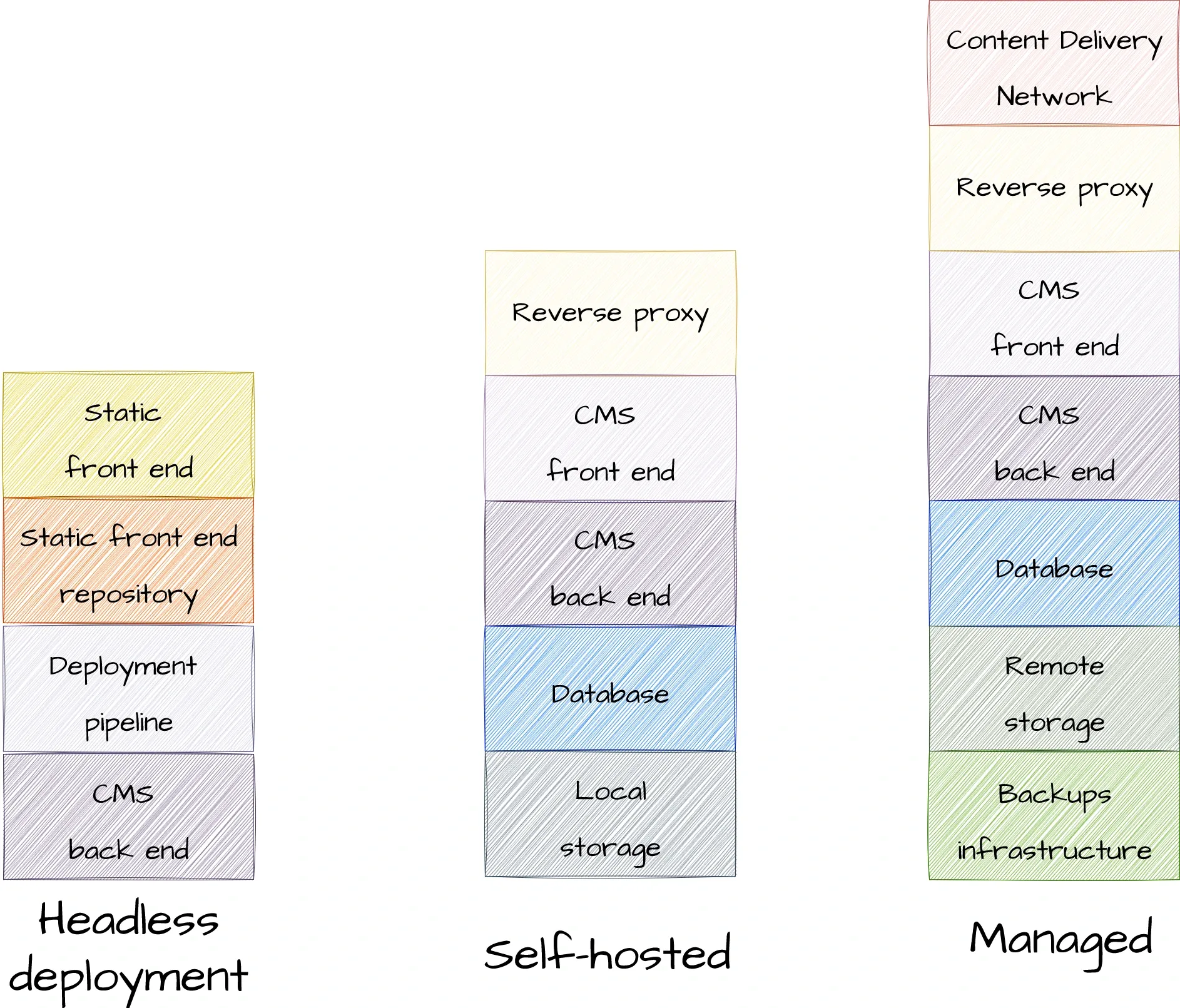

Let’s use this blog as an example: Misaligned Markets is built on a content management system called Ghost, written in JavaScript.[2]2 Ghost is open-source, so it can be modified and run on your own server or managed by a service provider. Originally, I self-hosted this blog using my own server configurations, but later switched to a managed provider.[3]3 My provider’s stack includes technologies I didn’t want to implement myself, like a content delivery network to serve my blog pages more quickly to users across the world.

We call these configurations stacks because the technologies that support a system often build on top of each other like levels in a building. Lower layers handle general, foundational work (like storing and transmitting data); higher layers handle specific tasks (like rendering a website or processing a login form). The further up you go, the closer you get to the user. Depending on your role — as a web developer, admin, or cybersecurity analyst — you might care most about a particular slice of that stack.

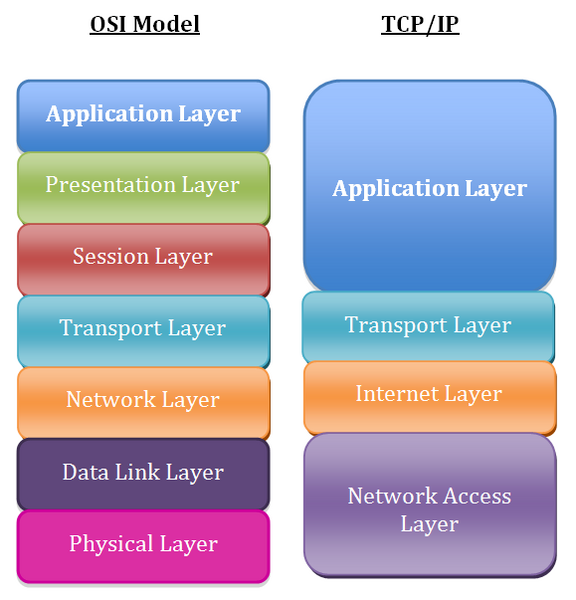

Stacks like the OSI model (Open Systems Interconnection model), are purely conceptual.[4]4 They weren’t built or deployed as-is, but provide a useful map of how different network layers interact — from physical cabling (Layer 1) up to the apps we use every day (Layer 7). Cybersecurity professionals and network engineers often use models like OSI to understand where failures, compromises, or misconfigurations can happen. This isn’t necessarily a description of how things work, but of how they can go wrong. That’s the sense in which I’m interested in capitalism as a stack. Not a literal one, but a conceptual system with interacting layers, each introducing its own affordances and vulnerabilities.

Most network stacks follow a similar model: at the bottom is the physical layer with cables, wireless signals, and fiber. Then, as data travels upward via protocols like TCP/IP[5]5, it gets packaged, transmitted, and finally rendered by applications (like a browser or email client).

There’s a genuine joy to networking; it’s magical watching two remote devices connect in order to make an application work. But there’s one hitch, implicit trust. As data travels up the “layers” of a network, each one must necessarily trust the ones below it. Many networked systems even broadcast their identity or share unencrypted data by default, making it surprisingly easy to hijack them or tamper with their transmissions. However, there’s some efficiency to this madness. It’s simply impractical for every layer to re-verify everything. If you’re running an online bank, you can’t inspect the Wi-Fi of every customer. Nor can you make users submit a genetic sample, recount their life story, and swear on their mother’s health just to log in. Not that any of this would be desirable, anyway.

This trust cuts both ways too. Users can also be tricked into visiting fake websites that look legitimate, because the protocols assume their choices are safe. Computers don’t “know” what people intend; they just follow rules. And that’s why cybersecurity professionals spend their time building guardrails and mitigations to patch over this foundational vulnerability.

Similarly, market capitalism is a system with protocols, or rules and procedures, that enable the transmission of abstract value. Like computer networks, it’s a system built on trust, and this trust can be abused to advantage oneself in malicious ways.

Much like the OSI model, I want to use the analogy of capitalism as a stack to capture:

- The ways market actors exploit different “layers” of the system to advantage themselves.

- How interactions between capitalism’s layers create the synergies that make market capitalism function.

- How market actors’ attempts to exploit capitalism’s layers can change how the system is configured. An open question I have is if behaviors like forced arbitration, loss of right to repair, or absence of data ownership[6]6 will end capitalism as we know it. Economists, like former Greek Prime Minister Yanis Varoufakis, argue this is already the case given how much social and economic power these practices give tech companies.

The four paradoxes of capitalism I introduced in an earlier post is my first attempt to build a “threat landscape” for capitalism. I intend to keep building on the paradoxes and use this “capitalism as a stack” metaphor to help us better understand market capitalism.

What does capitalism’s tech stack look like?

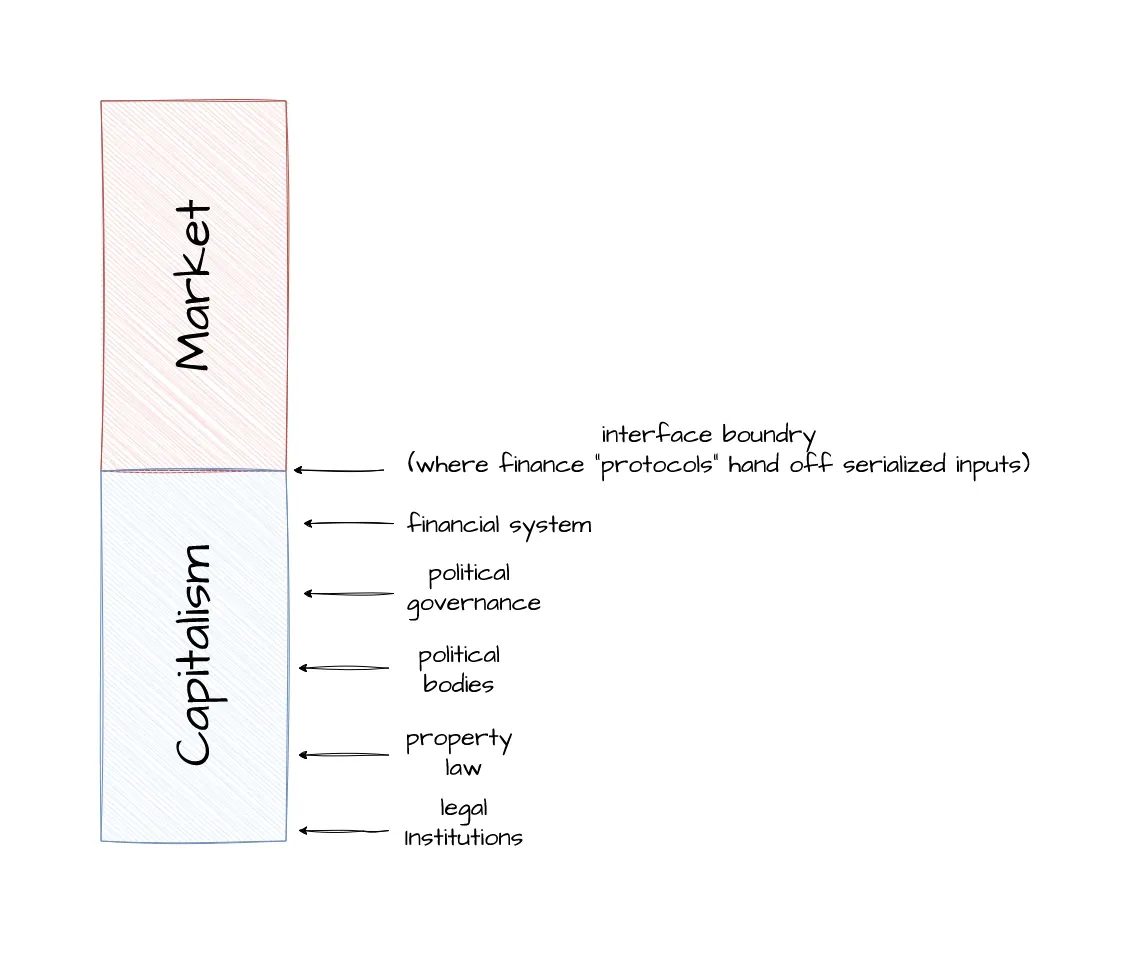

Since this is a constructed analogy, I don’t want us to obsess over how to literally define and map every element in a capitalist stack. Instead, let’s hold the general shape of this metaphor in mind and talk about functions within the stack. If we think of capitalism as “market capitalism” then, very broadly, there are functions which map to the “market” portion of the stack while others map to the “capitalism” portion.

As I’ve said elsewhere, capitalism is ultimately a system intended to track and codify ownership of things in order to facilitate capital accumulation. This means you can think of the capitalist slice of market capitalism as the legal, political, and financial infrastructure that allow for the metaphorical serialization[7]7 of real-world inputs in order to map them onto market processes. This is a fancy way of saying I hope you like JSON files, because you’re living in one.

Using references and pointers, like laws and contracts, capitalism is able to encode objects in the world as legal rights, financial entitlements, and standardized bundles of value that can be priced, bought, traded, and sold within markets. These logics can be applied to literally anything, though social norms and political activism place reasonable limits on this. There’s a reason why we can no longer legally buy and sell human beings, for example.

With this in mind, markets are then the application or interface layer of the system. This is where the consequences of capitalist serialization play out in real time, distributing goods, services, and investments, based on rules specified lower in the stack. Firms and services are then built on top of the “code” of capitalism, and what they can or cannot do is strictly defined by both the limitations and the “vulnerabilities” in this code.

As an aside, I know I’m using the language of crpyto bros, but this is just a metaphor designed to gesture towards opaque loci of power to illustrate their function. Crypto bros, however, are not operating at the level of metaphor. Unsurprisingly cryptocurrency is on the path to recreating and integrating with our existing financial system as these people thought it was a good idea to literally graft the failure modes of TCP/IP to those of capitalism.

The metaphor of capitalist serialization

Capitalist serialization isn’t the only function of the capitalist portion of the system’s stack, but it’s arguably its most important. It refers to the political, legal, and financial apparatuses that enable capitalists to be compensated for their inputs into the system. Serialization also allows for risks to these inputs to be priced. This is how your labor becomes a wage or a forest becomes a land deed. Even something as vast and complex as climate change is made legible to markets through damage functions which estimate how much future GDP loss corresponds to a rise in temperature.[8]8

Unlike serialization in computers, capitalist serialization is “lossy” meaning that it inherently excludes context that cannot be codified by capitalism or understood by markets. A forest turned into a land deed, for example, does not account for the role the forest plays for its local community and the harms of cutting it down. Capitalism’s ability to encode risk is supposed to offset this. However as damage functions illustrate, if the assumptions used to produce a measurement are inaccurate, then the market simply fails to capture the risk. This creates an arbitrage-like opportunity for anyone who can exploit this gap. Polluters keep polluting in part because attempts to get markets to price climate externalities have lagged in speed or accuracy.

A lot of analysis of capitalism focuses on the market layer. However, keeping the story of capitalism limited to the market is like trying to talk about a computer program solely based on its runtime behavior as opposed to its source code and dependencies.[9]9 To understand economic outcomes we need a clear grasp of a lot more than just supply and demand.

Capitalism’s serialization in action

Let’s build on what we’ve talked about so far. Capitalist serialization can turn an object into any number of abstract forms, encoding ownership, obligations, entitlements as well as what actions can be done with the object. The most common form serialization takes is commodification, or the turning of an object into a commodity—a thing that can be bought and sold. When commodities are sold, their ownership rights automatically transfer to the purchaser. When you go to the store and buy a phone, it’s yours (usually).

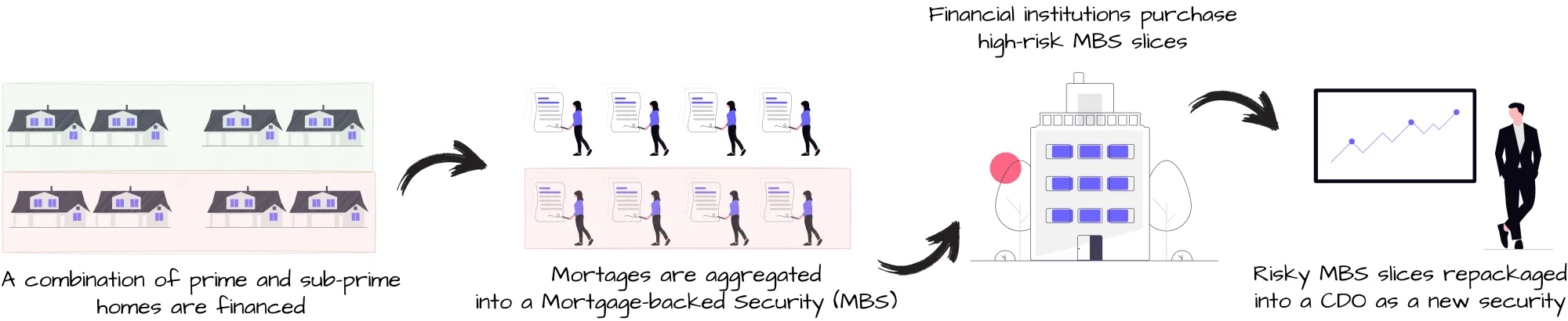

An object can be recursively serialized, like a commodity being turned into a financial object, back into a commodity, and so on. For example, mortgages codify claims on physical homes. But a mortgage itself is also an object that can be repackaged and sold from one bank to another, so that the new bank is entitled to the payments from the mortgage. This sell transfers not only mortgage payment cash flows, but entitlement to the house upon foreclosure.

The ability to influence what things are serialized and the manner in which they’re serialized requires access to legal and political influence. In most cases this isn’t an “exploit,” but a straightforward consequence of how the system works. There are times, though, where weaponization of this process is so egregious that the rules have to be rewritten.

In the lead-up to the 2008 market crash, banks engineered a class of derivative financial assets called Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs).[10]10 CDOs have existed in some form since the 1970s, although they grew in popularity with the 2000’s-era US housing boom. A CDO bundles together asset-backed securities,[11]11 then slices those into hierarchical segments called tranches in order to distribute returns (like interest payments) to investors. Tranches deliberately aren’t created equal in order to spread risk across the CDO. During the housing bubble, lower quality tranches consisted of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) with a higher risk of failure. These mortgage-backed securities themselves consisted of tranches created from pools of individual mortgages.

CDOs were invented because very few investors were initially interested in purchasing the lower quality tranches of existing MBS offerings. Banks wanted to make money selling the lower quality mortgage tranches and could clear debt off their books if they did. So someone on Wall Street came up with the terrible idea of buying these higher risk mortgage tranches and combining them into a new security.

Although CDOs consisted of portions of an existing security—remember tranches in a CDO come from an MBS which itself is a pool of mortgages—rating agencies whose job it was to evaluate risk treated CDOs like a brand-new security. Basically, tranches took risk values relative to the other tranches within the security they currently were in. It didn’t matter if a tranche consisted of lower quality mortgages from an MBS, the risk of each tranche was “reassessed” with proprietary models the moment it became part of a CDO.

This unholy cycle would continue up until the bubble burst. CDO tranches (which, again, are just tranches from mutiple MBS offerings), would be moved into CDO-Squareds. This is when a CDO tranche is added to a new CDO. That CDO-squared could then have its tranches moved into another new CDO (a CDO-cubed).

I shouldn’t have to tell you that doing this is the financial equivalent of shoving fine steak in a blender and mixing it so finely with bullshit that you can’t tell either apart.[12]12 From the rating agency’s perspective this was risk diversification. Pushing tranches into assets consisting of other similar risk tranches was a way to “isolate” risk. But in actuality this increased the demand for dodgy mortgages that would be added to MBS offerings, that would then be added to CDOs, to CDO-squareds, cubeds, quads, quints…[13]13 At some point this ability to serialize was deliberately used to hide deception. CDOs of this nature weren’t the only instruments that contributed to the crash, but by looking at how these CDOs were created we can see how, like hackers, capitalists can create “malware” that uses the system’s infrastructure for personal gain.

Updating capitalism

Like a computer system, capitalism should be patched to address issues like the ones we’ve discussed. Unfortunately, that’s where the utility of this metaphor ends. Unlike digital systems, there’s no over the air update we can push to create a system that works for everyone. I’m personally trying to learn about the history of land enclosure, abolition, and labor to understand a pattern historian Karl Polanyi called the Double Movement. This describes how resistance to capitalism’s excesses has helped shape the trajectory capitalism has taken.

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) and New Deal (1930s) Era arguably were our last economic “updates” in the US. they provide glimpses of what political and social mobilization can do. Antitrust laws, consumer safety, labor protection, removal of money from politics, and so much more. The norm up till then was that legal contracts and corporate economic freedom were the utmost considerations in any decisions around societal wellbeing. As US inequality rises, we clearly need a new Progressive Era, but one that’s not exclusionary. In a future post, I want to outline what that platform could look like.

Summary

- Information asymmetry drives activity in market capitalism. Profit-seeking activities incentivize market actors to take knowledge out of their heads and into the world where it can be useful.

- Similar to computer networks, which are open systems that implicitly assume trust by default, market capitalism has gaps in how rules are enforced and what harms people are aware of. These create profit opportunities that exploit people and place harms on the broader public.

- Market failures are like hacks or network failures where actors, following malincentives exploit information asymmetry about rules, harms, or psychology for personal gain.

- Capitalism, separate from markets, offers its own affordances and exploitable vulnerabilities that misintentioned actors can exploit. Thinking of capitalism as a metaphorical stack of technologies and protocols can help illustrate how capitalism is weaponized and hijacked.

- Capitalism codifies ownership of capital through a metaphorical “serialization” process which maps real world inputs and risks to abstract representations. These representations capture permissions and actions that can be done with the object.

- Capitalist serialization can be recursive. The Great Recession was partly caused by banks and investment institutions hiding risk through the creation of layered financial derivatives.

- Capitalism codifies ownership of capital through a metaphorical “serialization” process which maps real world inputs and risks to abstract representations. These representations capture permissions and actions that can be done with the object.

- Markets are an interface layer that can be considered the runtime environment for capitalism’s outputs. Work has to be done at the level of “protocols” and “infrastructure” to fix market capitalism’s undesirable outcomes.

Recommended resources

How market capitaism is formed

- Book: The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality by Katharina Pistor

- The Great Transformation The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time by Karl Polanyi

Breaking market capitalism like a hacker

- Book: A Hacker’s Mind: How the Powerful Bend Society’s Rules, and How to Bend Them Back by Bruce Schneier

- Book: Lying for Money: How Legendary Frauds Reveal the Workings of the World by Dan Davies

- Book: Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller

- Book: Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Climate Change by Erik M. Conway and Naomi Oreskes

- Book: Saving Capitalism From the Capitalists by Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales

- Article/Video: Competition is for Losers (Wall Street Journal, Y Combinator) Peter Thiel

Cryptocurrency’s re-creation of existing stack failures

- Article: My first impressions of web3 by Moxie Marlinspike

- Video: Line Goes Up by Dan Olsen

Affiliate disclaimer

Books on this page and throughout the site link to my Bookshop.org affiliate pages, where your purchase will earn me a commission that will go towards covering site costs. If you at all find the books I recommend interesting, consider purchasing through Bookshop, which shares profits with local bookstores. You can learn more about how you can support Misaligned Markets here.

- AFAIK, Shiller and Akerlof know next to nothing about computers, but understood that phishing revolved around deception. Regardless, they come pretty close to my understanding of how fundimental information asymmetry is to markets.

- Technically Ghost is built with more than just JS. It has a front end (what you’re seeing now) and a back end (what the server sees to process and transmit user information). Ghost uses different JS frameworks for its front and back end and like most websites has a front end stack that includes HTML and CSS.

- Shoutout to Jannus! This isn’t a paid endorsement, Magic Pages is just that good.

- The OSI model is a semi-depreciated model that was originally a proposal for how the internet would work. It's a close enough abstraction to today's network systems that it's still used for educational and diagnostic purposes.

- TCP/IP is the standard that gives us IP addresses, among other things. We’re going to talk a lot about it future posts because it’s an open protocol, owned by nobody, that unlocks billions of dollars of value in the economy. Innovations like this reveal how much progress depends on ideas open to everyone.

- These examples are somewhat arbitrary, but ones I often go to because I've been thinking about them a lot. You've probably seen them come up in other posts.

- In computing serialization is the process of turning complex data structures or relationships between digital objects into a more portable form (JSON is one such example). This in effect creates representations of the data in order to make it easier for other machines to read and transmit this information.

- How damage functions are calculated is matter of contention. William Nordhaus, who won the Nobel Prize for modeling the economic costs of climate change has been skewered by economists for the terrible ecological assumptions in his models.

- Runtime refers to the period of time when a program is executed or running operations. Analyzing how a program runs is useful, but far from the only analysis a programmer might do.

- Derivative assets are those that derive their value from another. For a mortgage-backed CDO to exist an asset, like a home, is turned into a mortgage, and that is turned into a portion of a financial instrument (a Mortgage backed Security or MBS). That MBS is then turned into a CDO. CDOs are the boogeyman in most explanations of '08, and they play a central role, but they aren't alone in causing the crisis.

- CDOs are actually a broader asset class, each one named after the asset-backed security that's part of it. There's an alphabet soup of names for bundles containing different assets (e.g. "CBO" is for bonds). In the aftermath of '08 CDO became a catch-all term for mortgage-backed securities.

- This is a metaphor inspired by a review that's been living rent free in my head for nearly a decade. Here you go.

- Okay, those last two were jokes... as far as I'm aware anyway.