AI hype is a mirror of market fundamentalism

Both AI enthusiasts and market fundamentalists gloss over the context needed to understand complex systems.

This is a follow-up to last month’s post LLM “intelligence” is a dark pattern. While you don’t need to read it, you’ll have a better appreciation of this post if you do.

About two years before I started Misaligned Markets, I encountered a blog called Both Brains Required by Duncan Austin, and for the first time in my life I felt like I wasn’t alone.

Okay I’m being dramatic, but Duncan, like me, is concerned with what he calls “externality-denying capitalism.[1]1” If you’ve taken a standard intermediate economics course, where market failures, externalities, and information asymmetry are treated as exceptions to how markets function, you’ll understand exactly what he’s talking about.

It’s worth noting that professional economists have more nuanced understandings of these issues, but just barely in my opinion. Policymakers, when approaching problems like climate change, tend to think in terms of “restoring” market function via mechanisms like carbon taxes. The idea with a policy like this is to put a price on the harms or risks from climate change so that market actors respond to them. If pollution becomes more expensive, then there’ll be less desire to produce it, so the thinking goes.

Attempts to “serialize[2]2” the ownership of market bads[3]3 are not inherently problematic, and have seen success. However, they tend to limit the imagination of policymakers trying to solve problems that ultimately exist beyond markets. Ultimately such policies alone are insufficient to address to scope of harms from climate change.

Ever since my first economics class, I had an inkling that something was wrong with the story that market failure and externalities were edge cases in how markets functioned, and that clever tweaks could “fix” them wherever they revealed themselves. I didn’t have the vocabulary at the time to articulate why, but years later, after committing myself to answering these questions, seeing that people like Duncan were on similar journeys made me hopeful.

Duncan does a great job of focusing on failures in economic reasoning, including economists’ failure to understand tradeoffs of ecological overshoot. But I’ve ultimately ended up in a different place than Duncan. I’m very narrowly concerned with how market actors are incentivized, by profit, to exploit structural asymmetries in society—something foundational to most market failure. Under this view, externalities are essential to how markets work, as they drive most profit-maximizing activity. You really only avoid them by being deliberate about what you allow the profit motive to act on. Failing to do this results in a world ruled by “Mammon.[4]4” This is my metaphorical name for runaway systems that narrowly optimize for a single goal at the expense of everything else.

The current iteration of market capitalism can be described as a blind and greedy optimizer (a “Mammon”) that seeks out arbitrage-like advantages where actors benefit from asymmetric knowledge or privileges at the expense of society. It’s not that these are the only type of exchange happening under market capitalism, but they’re becoming the most common as market actors zero-in exclusively on the paths of least resistance to profit.

Our current environment in part stems from policymakers and economists overly relying on markets on issues of trade, tax policy, and environmental harms. As a result, we’re now experiencing a perfect storm for extreme anti-neoliberal and hyper-neoliberal responses[5]5 to the system-wide crises we face. These responses are natural outgrowths of an oscillating, unstable system and will pour more fuel on the preverbal fire.

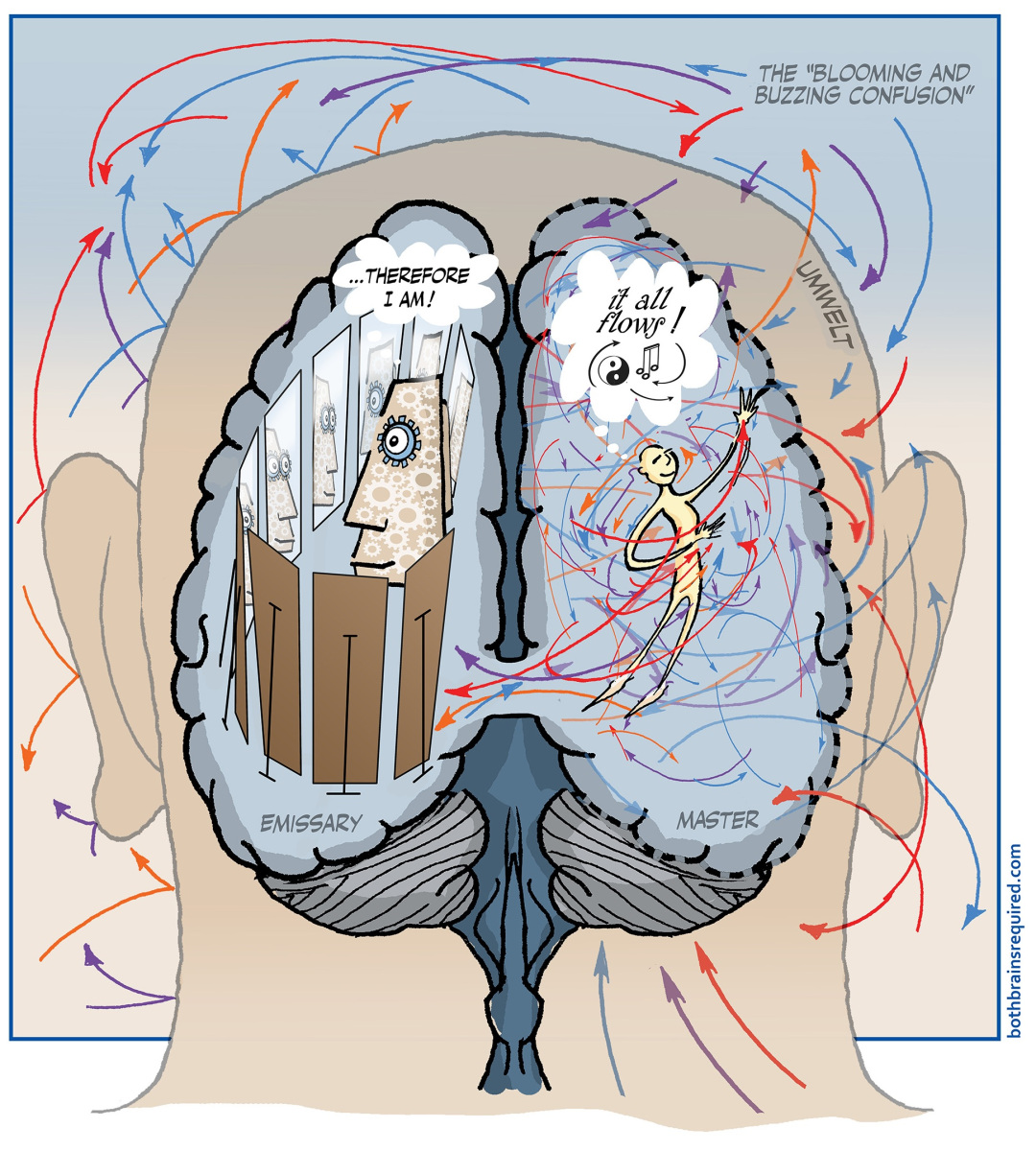

To some extent, I think this last point is where Duncan and I overlap.[6]6 The name of his blog, Both Brains Required, comes from the notion that we will metaphorically need both our reductionist, logical left hemisphere and our big-picture right hemisphere to solve our current challenges. Otherwise, we risk failing to grasp crises of our own design.

I’ve been thinking about Both Brains Required lately because I see some of the same metaphorical left-brained thinking in our collective conversations about large language models (LLMs). Coincidentally, AI boosterism is a great lens to explore market essentialism and how fundamentalism about markets can blind us to systemic harms.

The “left-brained” nature of AI boosterism and consumer capitalism

AI boosterism, especially of LLMs tends to come from viewing models themselves as the locus of intelligence within a chatbot. However, LLM intelligence, unlike human cognition, doesn’t emerge from nature. LLMs are statistical models that are trained on all of our collective knowledge, much of it pirated, containing more information than someone could consume in multiple lifetimes. Then models are evaluated by an army of thankless workers who teach models how to interact in a friendly and helpful manner. Finally, when models are up and running, engineers tune the subsystems and orchestration layer that ensure LLMs can reliably respond to user queries.

All of these people—the authors, the legions of internet users, armies of raters, and the engineers who maintain these systems—are effectively invisible cogs to the user, indistinguishable from the model itself. But without text from your favorite authors, LLMs wouldn’t have much to talk about. Without the working poor in the global south judging which responses feel most helpful and human, LLMs might as well just be autocomplete. And without engineers and real time subsystems, models would be functionally useless at runtime.

As I said in my last post, LLM service providers help cultivate the obfuscation or underemphasis of these layers of operation, effectively making LLMs as a technology a kind of dark pattern. The intended goal is to convince people to interact with models like they would a smart and trusted friend. By collapsing all of an LLM’s layers of operation, users are free to mistakenly attribute all (positive) LLM behavior to the model alone.

Although LLM providers actively encourage users to see models as the locus of intelligence, through marketing and the omission of these layers, they aren’t fighting an uphill battle to do so. Our left-brained anglo-capitalist culture naturally lends itself to an inability to appreciate any context surrounding how goods and services are delivered to us.

The modern consumer mindset

As the goods and services in society have become more complex, people’s relationship to what they consume has become more abstract. For example, I have no idea how to build many of the things in my office, like my computer monitor, keyboard, and microphone. Nor do I really understand any externalized costs required to manufacture or deliver these things to me. In the limited free time that I have, I’ve tried my best to understand the impacts of my consumption.

Realistically, though, I can’t do this for everything I buy, given my limited time and access to information. This is a perfect illustration of the fact that under capitalism we interact with markets in a way where functionally only the product exists. In our minds, what we buy is completely abstracted away from its components, the people who built it, and the supply chains that ensure its availability the second we click “add to cart.”

This resembles the dark pattern of LLM intelligence but in the context of how we interact with market capitalism as a system. The abstraction of an LLM’s layers convinces users to view language models as innate, standalone intelligences rather than tools that depend on human layer and other subsystems. Similarly, the abstraction of how things are made, and their potential external costs, contributes to the belief that markets innately “know” how to efficiently solve for people’s needs all on their own.[7]7

We’ll come back to that idea later, but there’s an entire literature within political economy which recognizes how capitalism creates within people a sense of personal distance from meaning and value. Under capitalism bosses reduce workers to cogs, consumers only care about the lowest price (externalities be damned), and investors see customers as little more than sources of income to be squeezed for excess profit.

Adam Smith, was one of the first to grapple with worker exploitation among other issues. At the very beginning of industrialization Smith expressed some concern with how the division of labor might drain purpose and meaning from an employee’s work, highlighting the sense of mental drudgery that came from repetitive and narrow tasks. This is recognized by many scholars as an indirect precursor to Karl Marx’s concept of alienation.[8]8 It’s debated how important this concern was to Smith;[9]9 he’s most known for talking about it in a single paragraph in Book V of the massive tome that is Wealth of Nations. However, Smith does bring up this proto-alienation concept several times across his lectures.[10]10

Marx, of course, has a more expansive version of alienation than Smith, given that he’s the originator of the term. For Marx, alienation can be seen as a core defining feature of capitalism. Like Smith, he’s concerned with workers, though he arguably expands the idea of alienation with commodity fetishism, which points to how goods derive properties independent of the factors of production that create them. That is to say, consumers, isolated from the broader processes of capitalist production, only understand goods as they appear in their final form, at the cash register. Our relationship to capitalism and to each other is mediated by this fact and by whatever psychological feelings manifest from what we consume. This completely obfuscates whose labor produces these products, the costs that workers and local communities may bear to bring a product to us, and other so-called externalities.[11]11 Though Marx himself never directly connects commodity fetishism to alienation there is a soft, but implicit gesturing toward a sort of symmetry between worker alienation and “consumer alienation” through the experience of commodity fetishism.

Arguably, one can view alienation and commodity fetishism as two sides of the same coin. Alienation collapses workers into cogs, while commodity fetishism blinds consumers from seeing attributes of a product as emerging from anything outside the thing being bought. This cumulative blindness is on display when people personify LLMs or, in other contexts, consume products that harm them in ways they can’t see.

The mindset of the market fundamentalist

In the last 20 years, there’s been growing cultural recognition that the post-Reagan/Thatcher revolution has pushed anglo-capitalist societies into a neoliberal world.

What exactly is neoliberalism? We’re not going to talk about that directly;[12]12 instead we’ll talk about market fundamentalism which arguably is a core aspect of neoliberalism. Market fundamentalism can be thought of as the idea that markets are the best (and maybe only) way to solve problems of access. Underpinning this idea is one I mentioned briefly early in this post: that markets are systems that innately “know” how to efficiently solve for people’s needs all on their own. This is very easy to believe if you ignore externalities and ignore the various non-monetary harms that come from market reductionism, like the quasi-moral injury Smith pointed to in his pin factory example.

I’m not implying that market fundamentalism and commodity fetishism are the exact same mindset, as these are two distinct terms with different focuses. However, market fundamentalism shares a similar metaphorical left-brainedness with commodity fetishism.

Markets as an emergent order

So, where did market fundamentalism come from? I don’t think it’s useful to try to pinpoint a single origin for modern market fundamentalism. If you were, though, the work of Friedrich Hayek is as good a starting point as any. Hayek is arguably the godfather of what we consider neoliberalism. Central to his work is his idea of markets as decentralized computational systems where efficiency emerges organically from within the system.

Emergence of complex (desirable) properties is one of the strong recurrent themes within Hayek’s writings, where he often contrasts emergence with unstable order imposed from top-down hierarchy. Hayek was mesmerized by a sense of self-organization he saw within systems like markets where people adjusted their behavior in real time around mechanisms like price. It’s the same story playing out in assumptions like cap-and-trade or carbon taxes as a climate change solution. If the price is too high, polluters won’t pollute, they’ll automatically change their behavior in response to market signals. Hayek’s obsession with decentralized emergence would actually motivate him to write a cognitive science book where this notion informed his views on consciousness and intelligence. I’m sure he’d see LLMs as a representation of his principles in action.

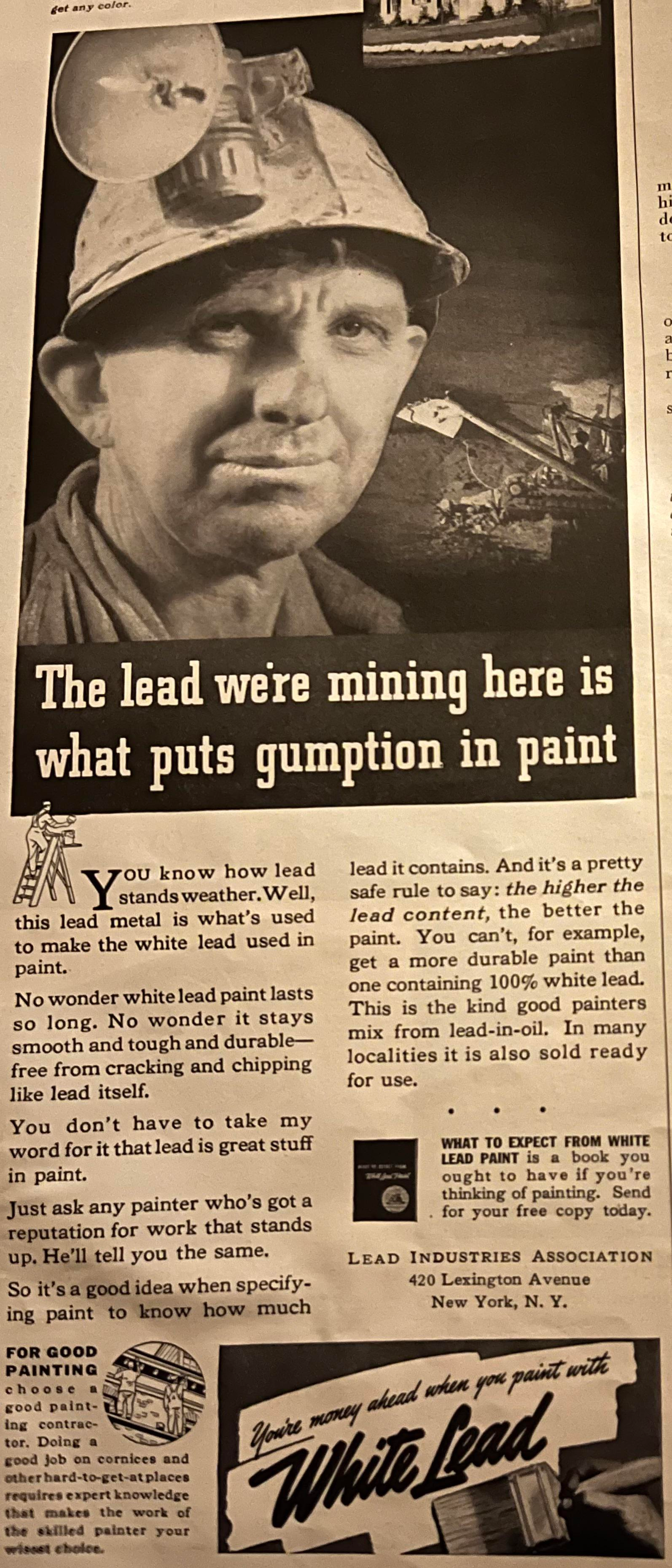

Featured: Hayek... probably

Why we need the right brain too

When I think about the story of markets as an emergent order, it feels seductive. Self-organizing systems do exist in nature, and prices do shape producer and consumer behavior without anyone telling anyone else how to behave. But there’s a lot more to the story. Failure to tell the missing half of how markets work reminds me exactly of the same mistakes AI boosters make when focusing on LLMs to the exclusion of the subsystems that enable models.

Recall in a previous post I listed 13 subsystems that LLMs use to ground and moderate their outputs. These subsystems arguably provide the bulk of an LLM’s utility. Furthermore, all of these systems must be maintained, in real time, by engineers to ensure that a model behaves as expected. Any story of LLMs that doesn’t talk about these subsystems is worse than incomplete, it has no grounding in how LLMs actually work because it attributes the work of these 13 layers (and the people who manage them) solely to the model.

Market fundamentalists make the same mistake with markets. Like with LLMs, there’s a whole “stack” of layers—institutions, laws, norms—that markets rely on to act on the world.[13]13 These are by no means neutral; societies have to give shape to how markets serialize or see the world well before anything like a price mechanism emerges.[14]14

What’s more is that actors within the market system can shape these layers. In fact, much of my blog is about documenting the ways market actors hijack their environment in their quest to maximize profits. See, for example, my blog post on the four paradoxes of capitalism. When we embrace market fundamentalism we are in fact embracing this competition over the hijacking of these layers, in addition to whatever social implications stem from reducing every domain to a “market-first” paradigm.

- I seriously recommend his blog. Please read it and encourage him to resume writing.

- Serialization is my term for how market systems label and organize objects in the world. This enables markets to "see" and act on things in the world. In the case of pollution, policy schemes like cap and trade turn it from an amorphous hyperobject into a bundle of liabilities that can be bought or sold on a market.

- A bad is just a sometimes used word for "externality." Bads are in contrast to market goods.

- The connection between my "Mammon" analogy and capitalism is not rooted in the common notion of greed. You can think of market capitalism as a greedy optimizer. Such systems maximize narrowly for a single objective at the expense of everything else. This can work well "locally" or within specific parts of the system while driving the whole system to failure.

- In my mind within the US context I'm thinking about tariffs (definitely anti-neoliberal) and some of the pro-AI policy we've seen from Trump II. There are other examples, though.

- That's not to say Duncan would disagree with any of my areas of focus; we've clearly taken distinct but overlapping approaches to a similar set of issues.

- I'm mainly drawing attention to the fact that abstraction of layers of labor for LLMs resembles a pattern in the broader economy. In the context of capitalism, though, this is not a dark pattern.

- I want to emphasize precursor. Smith's concerns are more narrow than Marx's though he brings them up several times. Marx was likely aware of Smith's concerns, but given how much capitalism had evolved from Smith's time Marx's concerns should be seen as distinct from Smith's.

- The debate centers on how essential the concern is to Smith, and where to place that concern within Smith's work. Given Smith's work prior to Wealth of Nations (Theory of Moral Sentiments) and his concerns with collusion and worker vulnerability it's clear to me he takes this concern seriously.

- Drawing on insights from Robert Lamb's "Adam Smith's Concept of Alienation," which coheres with how I've read Smith. But see here for a critique of that reading.

- It's important to note Marx never used this term "externality." It was coined by early neoclassical economists (after Marx) to include the logic of market failure within their framework to enable policy fixes.

- People often describe neoliberalism as capitalism on steroids, but this erases a lot of context. IMO neoliberalism is inextricably connected to fights over liberalism and freedom as an essentially contested concept. I don't want to have this discussion now. If you like long podcasts listen to Toby Buckle's four part series on libertarianism (part 1 is here).

- Hayek himself does not make this mistake directly, he spends time talking about institutions, though from what I've read this mostly seems prescriptive. I see Hayek as having a preferred social and institutional arrangement for markets and simply foregrounding that analysis in a lot of his work. I'd argue, contrary to Hayek, market competition includes competition over the rules of engagement, even when the state isn't captured.

- I know I keep using this word serialization, and it's very abstract. The point to understand is that markets act on contextless representations. For a hypothetical cap-and-trade one can represent "pollution" any number of ways: self-reported emissions, third-party audits, satellite tracking, and more. Which chemicals count? Market actors have an interest in choosing representations that benefit them.