Modern conflicts over property rights and commodification

The 21st century has become increasingly defined by fights over property rights and boundaries of commodification

Much has been said about “data as the new oil.” At first glance, this sounds like a fair comparison. Good data can allow for the productive functioning of machine learning algorithms, the digital “factories” of our age, but must first be refined. Furthermore, whoever has access to this oil has access to untold riches. But in my view, this is wrong. Data, as well as digital spaces and digital goods, are the new “land,” and fights over these resemble those over enclosure. Digital marketplaces and economies tend to use property rights to restrict consumer freedoms in order to maximize profits.

DRM and access in the digital age

For the earliest adopters of the internet, it promised a clean break from existing systems of control. Cypherpunks, technoliberterians, open sourcers, and technoptimists of all stripes had a hope that the net would be free from corporate and state interference. The internet itself was born of a stack of technologies—like TCP/IP (where IP addresses come from) and HTTP (how we access websites)—that were made by different people, are owned by no one, and facilitate the movement of billions of dollars every day.

For the most ardent believers of this vision, the internet would necessitate a rethinking of ownership and intellectual property. John Perry Barlow (1947-2018), co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) would go on to voice some of these considerations in a 1994 Wired Magazine article titled The Economy of Ideas (later republished as Selling Wine without Bottles). To say that this article (as well as Barlow’s later A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace) were contentious is putting it lightly.

While Barlow was wrong about how these tensions would resolve, he correctly identified contradictions within market capitalism that the digital economy would sharply exacerbate. Objects like code, programs, text documents, and photos by their nature are copyable and non-rival, meaning that sharing them does not restrict their access or quality and the costs to share them don’t increase for a producer. Researchers like Steven Weber have gone as far as suggesting that some things in the digital economy, like open source software, protocols, and operating systems are “anti-rival” as in sharing them benefits everyone. For example, distributing open source software creates positive network effects that improve the software for everybody over time—more access, more productivity, more knowledge of how to make the software better.

On the other hand, though, this non-rival nature of objects within the digital economy makes piracy trivial. For example, if every copy of Rush Hour: Back 4 More[1]1 is the same, then I have no reason to prefer buying it through Apple versus ripping a copy from my friend’s DVD. But if everyone did this at scale it would hurt the compensation of the movie’s staff. The same is true for any other digital media that’s actually worth consuming.

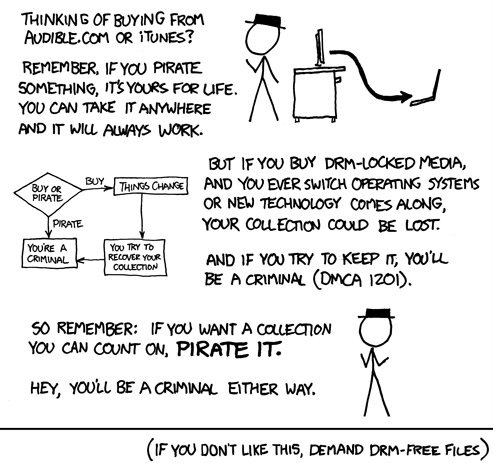

Rather than addressing this tension, like Barlow naively believed would happen, we’ve entered into a bizarre world where companies play a cat-and-mouse game with piracy groups, while leveraging technologies like DRM which effectively serve as mass surveillance. These cumbersome anti-piracy technologies end up incentivizing consumers towards piracy in the long run. Furthermore, companies lose the public opinion war when they apply draconian punishments to individual offenses or sue the wrong person. Ultimately, this is a state of affairs that not many people are happy with.

DRM or Digital Rights Management pre-dates The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), but the two are forever intertwined given that it’s the DMCA that gives DRM teeth. As early as the 1960s, companies began realizing the implications of software as a non-rival good and how this could impact their profits. It would however take many years and iterations before DRM took its current form. The final result is that ownership of many digital goods exists on a per-license basis, with no obligation for companies to guarantee long-term access to digital purchases. Furthermore, end users are restricted in the ways in which they can use a digital good like whether they can back it up, for example.

The battles over piracy are a skirmish in a bigger metaphorical war. Market capitalism is a system at odds with itself, where property rights enforcement both enables and restricts market activity. In a previous post, I highlighted this by outlining what I called the four paradoxes of capitalism:

- Property rights limit competition. Property rights allow for incentives and compensation to exist in market systems, but property rights inherently restrict where competition occurs, which can undermine market self-regulation and access.

- Property enforcement invites exploitation. If the state is too weak, then the cost of violating property rights is relatively low. Thus, the complexity of state-enforced property rights regimes tends to grow as markets mature. This, in turn, creates new opportunities to exploit the state to undermine competition.

- Markets reward secrecy but need transparency. Information has a tendency to diffuse to where it’s most useful, but markets reward secrecy through property rights. The consequence is a strong incentive for market actors to create information asymmetry and a reduced ability for markets to self-correct by identifying and iterating on useful information.

- Market success undermines market conditions. Markets can create Matthew Effects where the proceeds from winning market competition can be invested in undermining market competition, often by expanding property rights and exploiting the other paradoxes.

The four paradoxes can be imagined as dials which can be tuned toward market configurations that are either more or less concentrated. If a society—through its policies, consumer behavior, and business practices—favors excessive property rights protections, extreme concentration will follow, making it hard for new businesses to enter the market. Conversely, swinging too far toward perfect competition might make it hard for markets to form in a culture of possessive liberalism. I think the paradoxes are key to understanding conflicts over the digital economy in the 21st century. It is these tensions that make DRM a rational response for companies to not only ensure compensation for digital media, but to create opportunities for durable profits.

While some consumers and advocates have decried DRM and license-based purchases as the deliberate end of ownership, the simple truth is that market capitalism is fundamentally agnostic as to what is being bought and sold. Companies are under no compulsion to sell goods over licenses; they’re the producers and sellers of goods in the economy and get to freely choose what it is they sell. Furthermore, markets under capitalism are designed to codify what is even permissible to purchase or own, as the institutions that create property rights can freely design mechanisms to enforce those rights.

Attempts to enforce digital property rights actually reveal the code in the matrix of market capitalism. While property rights are useful to incentivize creativity, they are ultimately a fiction. Objects in the world don’t come marked with some attribute called “property.” Property ownership instead emerges through a process I refer to as capitalist serialization. Using legal references like patents, deeds, contracts, etc. market capitalism creates pointers that metaphorically bind abstract rights like ownership to some real world thing.

Whenever property rights enforcement occurs, it is the legal references and pointers that are the object of enforcement, as the system cannot “see” the real world object. DRM gives us a real time view of this process. While we as customers in the digial economy are purchasing infinitely copyable pieces of code, DRM is embedded into the digital media we buy to prevent or punish anyone using software in ways its owners don’t intend. Effectively, digital goods are serialized by literally merging them with their enforcement object so that the system can see and protect them.

Although many of the examples I’ve used so far seem frivolous, concerns over DRM extends far beyond digital media like movies, ebooks, music, and games. One area of growing significance is over the “right to repair,” where companies use DRM or patents to make it difficult for customers to service hardware integrated with complex software—examples include cars, tractors, and medical devices. Sometimes this is done deliberately, as companies benefit when they limit who can repare a device (assuming it’s even intended to be repared). Other times, as was the case with Second Sight, a bionic eye manufacturer whose customers were faced with imminent blindness when the company was shutting down,[2]2 it’s a regrettable result of business circumstance and a lack of legal obligation to provide customers recourse.

With software and computing becoming a ubiquitous part of many critical systems in our lives, we should expect this tension between competing property rights—those of producers and those of consumers who expect to “own” an end product to intensify. This conflict will not just shape the nature of capitalism, but because enforcing property rights requires tracking, and restricting the flow of information, it may very well shape the future of the internet and our broader society. Unfortunately, issues like these reveal that while there is indeed subtle tension between intellectual property enforcement and consumer welfare, capitalism cannot implicitly tell us how to solve it. The system is compatible with societies with both excessively strong and weak property rights.

Data privacy and the end of consumer surplus?

Perhaps the thorniest question at the center of the entire digital economy is “who owns data?” Who owns the facts about you or your online activity, including second-hand information about you gathered from your friends? Companies like Facebook provide services that generate data on their platform. Traditional understandings of ownership grant them the right to do what they wish with this data, as they put in the “work” to generate it. This work includes refining data gathered from non-users via internet trackers, or as was the case in 2011, using psychological tricks to get Facebook users to narc on all their friends who weren’t using Facebook at the time.

Sometimes the purpose of collecting data is as straightforward as sharing it to refine it for training purposes. But other times, data is used in a way that will disadvantage consumers in the future. For example, I talked before about GM’s strategy to sell information from their on-board telemetry to data aggregators which directly impacted drivers’ insurance prices.

In 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) began investigating what it referred to as surveillance pricing, which is the use of individualized data to prepare individualized prices for a specific person. This practice isn’t new, per se, nor is it the first time the FTC has broached it. The agency has produced reports on issues around broader topics like big data and targeted ads. This is the first time, however, that the agency has reached out to industry on this topic.

Personalized pricing, if effective, will allow companies to use data they’ve collected under ambiguous circumstances to conduct what economists call first-degree price discrimination which is using knowledge of a specific individual’s highest acceptable price. If done in aggregate this will eliminate consumer surplus and take away the ability for competition to keep firms in check. Some economics textbooks often present consumer surplus as a psychological “nice to have.” However, because consumers use their surplus for other things—like saving, paying taxes, or spending elsewhere in the economy—an increase in the number of transactions that reduce consumer surplus is a net bad for society, both economically and in terms of social wellbeing.

Platforms and chokepoints

From the mid-2000s onwards, the digital economy has become increasingly defined by the actions of a small handful of companies that have sought to create horizontal monopolies. These include Google, Apple, and Microsoft which function as platforms or on-ramps to a broad number of services that are necessary for navigating the 21st century. From operating systems, email, productivity tools, and a growing number of third-party applications the grasp of these companies is inescapable. This means that both access to these services and the profitability of offering such services have become gated by a small number of hands. There is also evidence, as antitrust litigation shows, that some of the biggest players in this space abused their positions to prevent competition.

Some, like theorist Nick Srnicek have referred to this state of affairs as “platform capitalism.” Others, like former Greek Prime Minister Yanis Varoufakis have gone further, calling our modern moment “technofudalism.” While there is a question of how warranted these names are, there’s no denying the power that these companies have; not just as market actors, but as gatekeepers of information, communication, and access to many of the necessities of the 21st century.

The defining feature of tech services as platforms is perhaps their dual nature as enablers of economic activity and as market participants. Platforms like Amazon serve as both “marketplaces” where other, usually smaller, producers can sell their goods and as vendors in these same marketplaces. Within these companies’ platforms there’s a tension of rigging the rules in favor of the broader business at the expense of users. Companies start out treating customers and sellers well, but over time, just like with casinos, the house tends to win in the long run. Activist and author Cory Doctorow calls this process enshitification, where a service—usually backed by a mountain of VC money—starts off highly beneficial to users, but over time, rakes back the benefits which attracted these users as the company’s market position becomes entrenched.

Enshittification is the natural result of a business model lauded by Silicon Valley called “blitzscaling” which encourages adopting high risk practices to grow the valuation and market position of a startup in order to crowd out competitors. Such practices might include providing temporary perks to users, out-subsidizing competition with excessive VC spending, regulatory arbitrage, and more. As Silicon Valley tycoon Peter Thiel puts it, “competition is for losers.” The goal is to do whatever needs to be done in order to be first to market and build a monopoly. Blitzscaling isn’t always such brutish business, but the rush to be first often requires “moving fast and breaking things.” As entrepreneur and writer Tim O’Reilly reflects:

The problem with the blitzscaling mentality is that a corporate DNA of perpetual, rivalrous, winner-takes-all growth is fundamentally incompatible with the responsibilities of a platform. Too often, once its hyper-growth period slows, the platform begins to compete with its suppliers and its customers. Gates himself faced (and failed) this moral crisis when Microsoft became the dominant platform of the personal computer era. Google is now facing this same moral crisis, and also failing.

Enshitification doesn’t just frustrate users of platforms, but can entrench monopoly power. Consider, for example, Amazon’s former most favored nation clause which forbade third-party sellers from offering goods at a lower price off Amazon. Given the size and scope of Amazon’s user base, not having a presence on Amazon could be detrimental, so sellers complied, raising prices everywhere else. This is far from the only thing Amazon has done to take advantage of the precarious position sellers often find themselves in. A Reuters investigation found that Amazon India used internal data about goods sold on their platform—information gathered from sellers and that no other competitor would have—to create private label brands that got preferential treatment on the platform.

For the past 40 years, antitrust has predominantly been seen as a “consumer welfare” issue where consumer welfare is seen as the ability to unfairly price goods to the extent it harms consumers and leaves them without recourse. However, given the growing scope of power that platforms now enjoy, antitrust enforcement as of late has become increasingly reevaluated, by people of all political persuasions.

Part of the reason the consumer welfare standard has been seen as incomplete is that market power has effects beyond the prices consumers face. The ability of tech monopolies to buy out alternatives has the ability to limit where internet users can express themselves by stifling alternative communication platforms. It has also increasingly given way to monopsony power. Monopsonies refer to markets where one buyer can choose from a wide variety of sellers. Econ 101 has treated monopsonies as fairly rare, niche markets. One example you might find in an economics textbook is the world of one-of-a-kind paintings where one rich fanatic might be the only buyer for a select portfolio of works. However, some economists have been aware since at least 2003 that labor markets may naturally tend to function as monopsonies, at least locally. Today, the concentration of market power that digital platforms have illustrates that this is increasingly becoming an issue within the digital economy.

As a growing number of workers enter the online gig economy and digital marketplaces as sellers of apps, creative works, or of their own labor, they are funneled to one of several dozen platforms where they can make money. Submitting to the rules of platforms often means pretzel-twisting your way into compliance with an ever-shifting set of changing rules and payouts. This is on top of having to pay a portion of your earnings for the privilege of using the platform; usually in excess of 20% of what you make. While participants in the digital economy have grown accustomed to this compensation structure, incidents of perceived overreach have drawn attention to the asymmetric nature of users’ relationships to digital marketplaces and platforms.

Cory Doctorow and Rebecca Giblin refer to this as “chokepoint capitalism” as platforms, serving as middlemen, create and implement an increasing number of rules and fees that nickel-and-dime the very users generating value on their platforms.

To illustrate this with a rather crazy example, in 2024 Patreon, the membership monetization app which many creatives use to fund their work, announced a fee increase that would be imposed on any subscriptions from users on iOS. Luckily this got paused as a result of a court order, but originally Patreon members were expected to choose to either absorb these costs directly or let their subscribers pay higher prices.

While Patreon is no stranger to increasing fees on its members, this fee was actually imposed by Apple who has absolutely no relationship to the company outside the fact that Patreon can be accessed from the Apple App store among other places. Apple’s attempted 30% cut also dwarfs that of Patreon which is, as of time of writing, capped at 12%. Although this is simply a straightforward application of Apple’s rules, the optics of Apple’s tax are bemusing. By attempting to take a bigger cut than Patreon itself, Apple seemed to be suggesting it provided more value to Patreon users than the platform itself. Relying on income from digital marketplaces and platforms like Apple and Patreon requires users to submit to rules that are seemingly arbitrary and can change on the fly. This is why this blog is hosted using Ghost, an open source blogging platform that can also manage paid memberships.[3]3

Property rights are eating the world

As I’m hoping this blog post illustrates, naïve and absurdly straightforward interpretations of property rights are slowly turning the digital sphere into what many internet users are casually calling a dystopian hellscape. All of this is without even going into the contentious issue of AI and asymmetric enforcement of property rights. Internet communities, without access to DRM and the force of law must effectively accept that the behemoths building today’s foundational AI models (like OpenAI) will have access to lawyers who can “clean up the mess” as these companies move fast and break copyright law in one domain while strengthening elsewhere in their favor. You can’t, for example, legally access the weights to the models trained on everyone’s data and would be sued into oblivion if you tried.

This tension within market capitalism allows for the ability of companies to use IP law defensively to prevent competition or extract rents. The state can be compelled to punish economic alternatives, if it can be convinced that these profit or benefit from ideas that sufficiently resemble those of an incumbent, regardless of how broad or ill-defined the IP violation might be. The state can also be used to help companies nickel-and-dime users by commodifying their data at the expense of consumer surplus and to tax an increasing number of activities happening online, simply for originating from a platform.

This means the law can be encoded in a way that decides which ideas are allowed to exist and ensure existing market actors receive the value they feel they’re entitled to by being first to market. Much ado is often made of regulation creating barriers to progress, which is a concern, but a good deal of innovation is stifled well before the development of regulation, as the logic of property rights enforcement creates undue difficulty in entering the market or iterating on existing ideas.

The fact this is a feature of market capitalism that is up for discussion—many papers, briefs, policy analyses have been written on this—points to the subtle contradictions that stem from the marriage of markets and capitalism. While we may speak about capitalism and markets as a single monolithic, singular system that simply emerges from aggregated human preferences and behaviors it isn’t. Running market capitalism requires a series of deliberate legal, political, and economic tradeoffs, and it will always take different forms based on the time and place it exists. In future posts we’ll take a deeper dive into the paradoxes of capitalism and the many tradeoffs they present for a capitalist society.

Recommended Reading

- Article: Fencing off Ideas: Enclosure & the Disappearance of the Public Domain by James Boyle

- Book [Free]: The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind by James Boyle

- Book: Virtual Competition The Promise and Perils of the Algorithm-Driven Economy by Maurice E Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi

- Book: Chokepoint Capitalism: How Big Tech and Big Content Captured Creative Labor Markets and How We'll Win Them Back by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow

- Book: Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It by Cory Doctorow

Affiliate disclaimer

Books on this page and throughout the site link to my Bookshop.org affiliate pages, where your purchase will earn me a commission that will go towards covering site costs. If you at all find the books I recommend interesting, consider purchasing through Bookshop, which shares profits with local bookstores. You can learn more about how you can support Misaligned Markets here.

- If this is a thing, I refuse to beleive it'll be named anything else.

- Purportedly Second Sight users were saved from the worst-case scenario when Nano Precision Medical acquired Second Sight’s intellectual property.

- This blog was originally self-hosted on a personal server, but I moved to Magicpages.co (thanks Janus) to save myself some time. The amazing thing about open source apps is you’re free to use them however you want. I’m not obligated to use the official Ghost platform run by the Ghost Foundation; nor do I have to manage my own instance.